America is actually geographically depolarizing

After a spate of Senate Republican victories on Democratic turf, progressives are now citing geography to discredit the democratic outcomes of the United States Senate.

Note: This is a repost from a Statehood article published on December 17, 2020 titled “The geographic polarization myth”

-

One of the most fashionable frames that have emerged over the last two years to understand the changing American electorate is one premised on the concept of geographic polarization, the idea being that the sorting of Americans into denser urban areas contrasted by fewer Americans living in mainly rural areas is the dominant force not just shaping partisan coalitions but also distorting American democracy.

Academics have been researching geographic polarization and partisan sorting for years including how the salience of social and cultural issues contributed to the modern alignment of the parties as we know them where Republicans have come to concentrate themselves in non-urban spaces and Democrats in more urban spaces. A previous post I wrote touched on this in tracking how Senate Democrats went from dominating rural America in the 1970s before gradually becoming the party of urban America. But it’s only within the past two years that the rather anodyne concept of geographical polarization has been adopted by reporters and pundits alike as not just a way to observe the ebb-and-flow of the American electorate but as a kind of all-encompassing string theory to tacitly and sometimes explicitly delegitimize democratic institutions, specifically the United States Senate.

The emerging narrative in progressive punditry and dripping into mainstream reporting is that the Senate is rigged against the Democratic Party. Since more Democrats now tend to sort themselves into denser urban areas and Republicans tend to sort themselves into less dense suburban and rural areas, and since the U.S. grants equal suffrage to the States regardless of their population as a check on the consolidation of central power, Democrats’ current coalition makes the Republican advantage in the chamber nearly insurmountable.

The polarization indicated by cities voting more heavily Democratic and rural towns voting more heavily Republican has had an asymmetrical partisan impact, as critics like Ezra Klein put it. FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver characterized the Senate as having a “rural skew”. The Atlantic’s Ronald Brownstein and The Economist’s G. Elliot Morris have gone as far as tacitly condoning whatever hypothetical political violence occurs from anyone who happens to share their framing that the Senate is rigged against the Democrats. The poetic version of the same narrative, subscribed to by Brownstein especially, casts urban America as something of a racially, culturally and morally superior constituency and non-urban America as a backward, inferior and outdated anchor holding back America’s true majority from emerging in the Senate and beyond.

The study of how Americans sort themselves into the places that they do has been an interest for political scientists for a while. One relatively contemporary correlation that’s emerged over the last 50 years is the relationship between density and partisan preferences. People who tend to vote for Democrats tend to live in denser areas and those who tend to vote for Republicans live in less dense areas. A sound and logical conclusion when observing this correlation that has grown especially tight within the last twenty years is, well, Americans want to live in places where the family down the street or the cashier at the drug store around the corner is more likely to share their beliefs. Or alternatively, that people aren’t so much sorting themselves because of politics, but that social and cultural preferences that people have tend to correlate with their politics and that this is why we’re experiencing the kind of “geopolitical” polarization we see in county-level election results.

Political scientists Greg Martin of Stanford University and Steven Webster of Washington University think differently. They make the case that most people aren’t opting, say, for a pick-up truck or a home with a one-acre lawn and a two-car garage because it overlaps with their political preferences, but that in reality most people make decisions about where to live based on their jobs, the needs of their families, among other things. In their study, they compared Democrats with those of demographically comparable independents and Republicans to see if there was a material bias in the rate at which either group of partisans moved to more dense or less dense neighborhoods. In a simulation they ran, Martin and Webster found that if the rates at which partisans sorted were basically set on autopilot, that geographic polarization would significantly decrease.

So the rates at which Americans are moving from Place A to Place B isn’t the cause of geographic polarization. There are two other possibilities.

First, political coalitions have changed. For a considerable portion of the twentieth century, Democrats dominated federal politics in part by balancing an enormous coalition between southern Democrats and northern labor Democrats with which liberal northeastern Republicans and western Republicans could not compete, frequently unable to crack 40 seats in the U.S. Senate. The South began drifting toward Republican presidential candidates in the nineties — and in the aughts in the U.S. Senate — leaving the Midwest and a more friendly Northeast as the party’s bastion of support. But over the last ten years, Republicans have put up an enormous offensive in the Midwest. In 2010, Democrats held 16 of the 24 seats across Midwestern states. In 2021, they will hold eight. In 2010, Democrats held 13 of the 32 seats across Southern states. Next year, they will hold seven. With a Democrat in the White House, it is true Democrats were on the defensive as is often the case with whichever party holds the presidency. In-parties tend to either let their guard down or suffer from less enthusiasm compared to an opposition eager to stick it to the sitting president. It’s worth noting the South and the Midwest account for 60 percent of the U.S. population and 56 seats in the Senate. If Democrats want to retake the Senate they don’t need to dominate these regions, they just have to restore something resembling a meaningful presence in them.

The second likely reason for geographic polarization takes us back to Martin and Webster who find that the places to which people move influence their partisan identity to more closely align with their new location. Why this is precisely the case is not clear, but a combination of social-economic interests, interaction with new members of the community, job and educational opportunities could be factors.

This reminds me of some of the exit polling found from the 2018 election in Texas (where I live). The conventional wisdom is that the voters who have moved and are moving to Texas are the people who are electing Democrats and turning the state purple. But when voters were choosing who to send to the Senate between Republican Sen. Ted Cruz and Democrat Beto O’Rourke, the two candidates virtually split the vote among voters born in Texas, 51-48 percent for O’Rourke. Among voters who moved to Texas, Cruz won those voters over 57-42 percent.

The popularity of approachable, consumer-forward data journalism that heavily relies on a kind of borderless aggregation that tries to make sense of the electorate from a stratospheric level can often lose sight of the fact that what we’re talking about are people, whose political preferences are malleable, who are themselves full of seeming contradictions, whose choices cannot be reductively summed up based on their sex or race or the car they drive or whether they’re more likely to live closer to a Cracker Barrel or a Whole Foods. More importantly, a more accurate portrait of the American electorate will survey voters in the districts and states they live, not an aggregate of them. If you’re not paying attention to the States, you’re not paying attention.

But here’s the other problem with the geographic polarization narrative: Americans are actually geographically depolarizing!

The premise of an urban-rural divide is yet another simplistic dichotomy audiences are forced to accept even as more than half of them sit in suburban homes. The omission of the suburbs, the centerpiece to understanding the American electorate from an urbanity point of view, follows a trend in popular journalism today that fixates on the extremes and criminally omits the vast center, painting a dramatically misleading portrait of malignant stratification that doesn’t exist. Fixating on the extremes of any given spectrum is a recurring way popular news media have lured audiences. Contrasting polar opposites of anything and characterizing it as representative of a whole is prime sensationalism that gets the kinds of clicks and shares you’d expect.

For example, the fixation of constantly contrasting the very poorest Americans and the very wealthiest Americans while omitting 75 percent of income earners distorts our sense of inequality and ability to address the issue. The fixation of contrasting the public opinion of the youngest adults and the oldest adults while omitting anyone between the age of 25 and 64 distorts our sense of social and cultural attitudes that better represent our communities and the country. The urban-rural divide narrative is no different. It omits the suburbs because the suburbs are just about evenly split between the parties. Since they are evenly split, they tend to defy the rigid assumptions of ideological pundits who have every incentive to operate on the polarizing premise that the best way to publicly understand the electorate is by stoking resentment toward and between Americans who live in cities and those that do not.

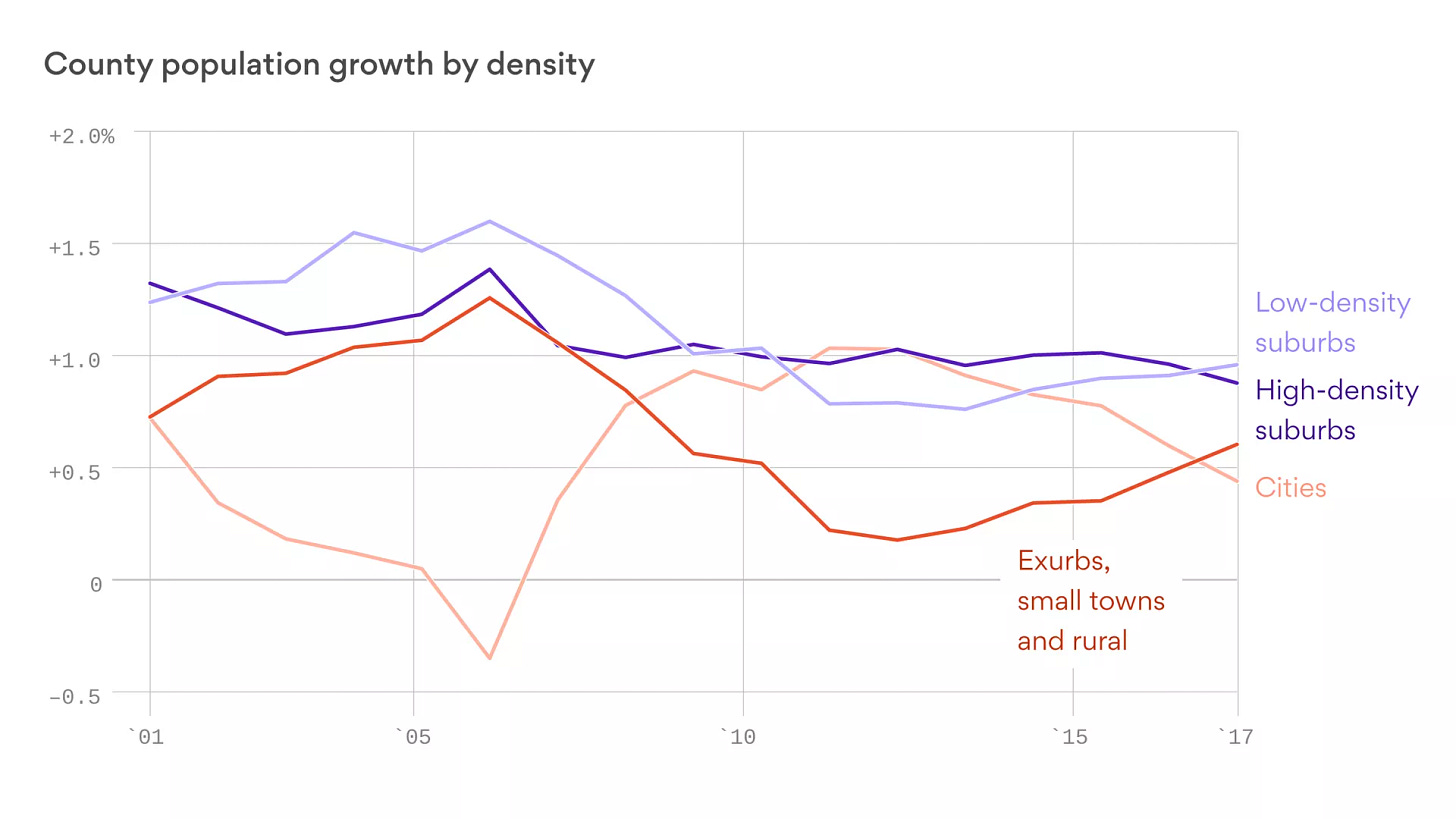

This is especially a problem because over roughly the last decade the share of Americans living in the suburbs, exurbs and small towns has risen as the share of Americans living in big cities has declined. The U.S. is and has been suburbanizing, not urbanizing.

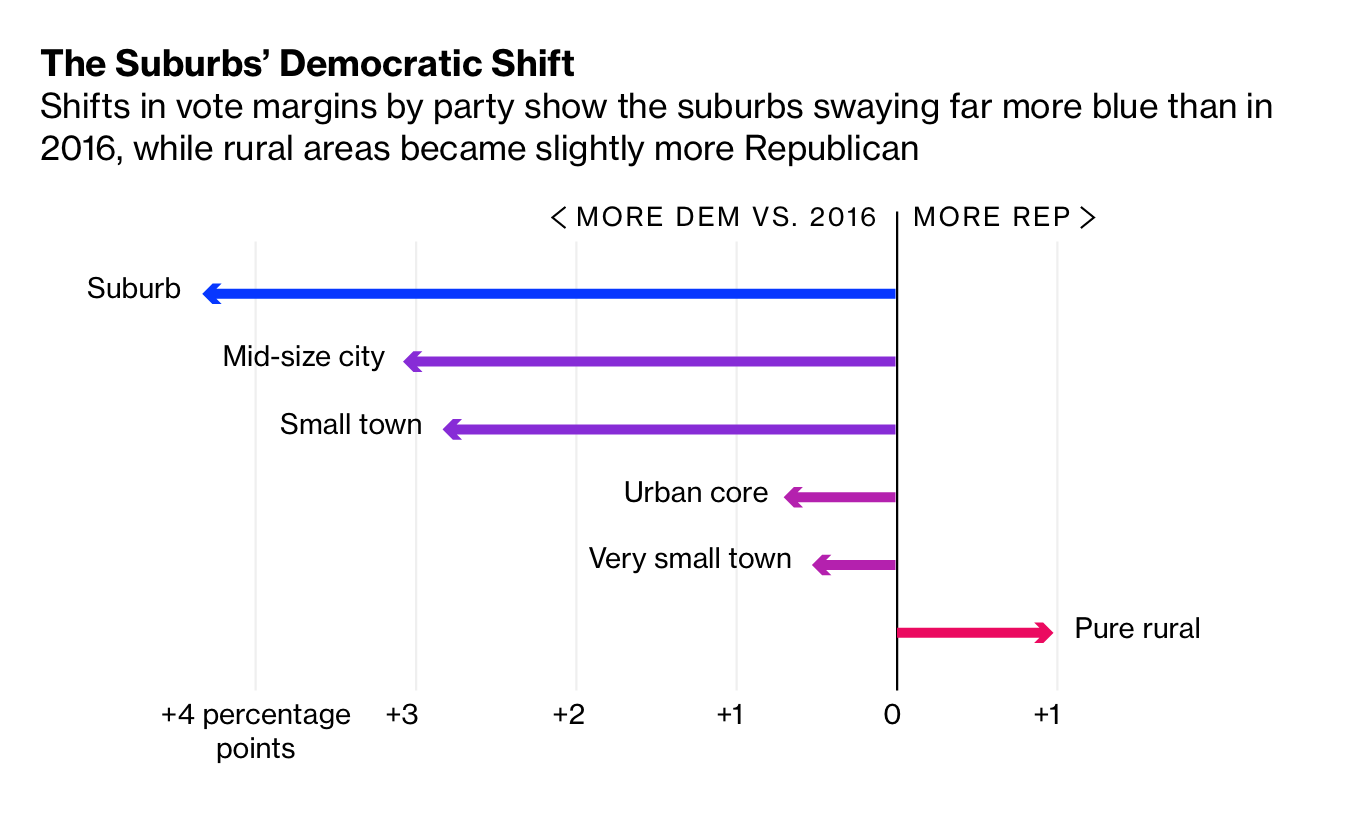

As I’ve written, while the looming influence of the suburban vote isn’t new to American electoral politics, when one looks exclusively through the lens of political geography the predominant divide emerging is really between urban and suburban localities. A prime but not all-encompassing indicator of this was the Biden campaign not only winning back for Democrats what we commonly conceive of as the suburbs just outside of urban cores but he also gained substantially among mid-density suburbs and further out exurbs. The Trump campaign was able to turnout rural voters again at impressive rates, but what fundamentally decided the presidential election in key battleground states was the Biden campaign’s ability to contest and win a much broader suburban constituency.

Geographic polarization also implies that urban areas are becoming more Democratic and less urban areas are becoming more Republican. When looking at how cities in existing deep blue states voted in the presidential election — Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, New York City, Philadelphia — one finds Donald Trump actually increased his share of the vote in all of these cities. The urban areas where Trump performed worse were in cities like Houston, Denver, Charlotte, Atlanta and Phoenix, all cities in red, purple or recently reddish-purple states that ostensibly are trending blue. In 2020, Democrats continued their suburban rebound from 2016 though that came with mixed results. Biden was able to flip enough localities in enough states to earn him a roughly 46,000-vote lead to win the presidency, but House and Senate Democrats downballot markedly underperformed costing the party an unexpected 10 seats in the House and several prospective Republican seats in the Senate.

So we know city voting margins haven’t changed much. We know Joe Biden was able to narrow Republicans’ advantage in at least some suburban localities but it remains to be seen if congressional Democrats can continue to do the same. We know more Americans are moving to the suburbs, exurbs and small towns. We know moving isn’t contributing to relative geographic polarization. We know America is geographically depolarizing into relatively less liberal spaces compared to cities. We know that political coalitions have both changed as a result of increased competition in the House and Senate after decades of rule by the Democratic Party. And we know there’s a relationship between new residents to a locality and those new residents adopting the partisan identity of that locality. So why are an unrepresentative, insular class of college-educated urban liberals who work in news media now casting the United States Senate as a "distortion" of democracy?

It’s because their preferred side (and frankly mine as well) is losing elections.

A year ago, Matt Yglesias offered this curious little frame:

The disproportionality of the Senate has long mattered in American politics. But it didn’t matter in a particularly partisan way until recently. Overrepresentation of rural voters manifested itself mostly in bipartisan support for things like farm subsidies, the Universal Service Fee that’s charged on phone bills, the Essential Air Service, and other relatively small-bore ways in which the federal government caters to rural interests. But the drift of white, working-class voters into the Republican camp has increased the scale of the tilt.

Yglesias frames the “overrepresentation” of smaller states as a dynamic feature that changes based on bipartisan support of legislation. But equality among the States in the Senate is a static feature. It doesn’t change, but parties change. Parties navigate how best to adopt a platform for which there is a demand. When Yglesias says representation in the Senate “didn’t matter in a particularly partisan way until recently” what he means is it didn’t matter to Democrats.

The Republican Party went 26 consecutive years in the Senate minority between 1954 and 1980, in part, because Senate Democrats dominated representation in rural states, urban and suburban states. Democrats would again win over sizable shares of rural states in their 1987-1995 majority, and to a lesser extent, the first half of their 2007-2015 partial supermajority — all while appealing to and winning over voters in the lion's share of urban states.

In 2009, Democrats held seven of eight seats across North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana and Arkansas. Today, they hold one.

When Yglesias writes that “The drift of white, working-class voters into the Republican camp has increased the scale of the tilt” he’s getting at the crux of his argument which is a partisan one. When it is said that geographic polarization is distorting the Senate as a result of the overrepresentation of rural states, what they mean is that rural states are now electing Republicans. The distortion of democracy Yglesias observes is Republicans winning a competition whose rules have not changed in a country where Americans are moving to less dense places. The case against the Senate boils down to a simmering greivance with a constituency that delivered Democrats majorities but decided to vote differently than they had for the last fifty years.

Nate Silver framed the U.S. Senate as a problem for Democrats briefly suggesting that the party could appeal to rural voters but that their structural disadvantage in the Senate wouldn’t be remedied until the party won back enough power to admit new states that favor them.

Competing to win over (rural) voters and not admitting new states at the slightest encounter with political adversity as parties have been doing for the last 100 years sounds like a good idea! Though, as I’ve said before, with the rise of the suburbs and more elections looking to be decided along a gradient urban-suburban field, Democrats should aim to pick up seats where they’re making inroads (the suburbs) and cushion their Senate coalition by remaining competitive in rural states. This is basically the opposite of the Senate Democrats’ strategy over the last fifty years where the party appealed to and won in urban and rural states while cushioning their majority with suburban states seats.

Ezra Klein frames competition differently. He argues because of this “distortion”, Democrats have to appeal to the center in ways Republicans do not.

Put simply, Democrats can’t win running the kinds of campaigns and deploying the kinds of tactics that succeed for Republicans. They can move to the left — and they are — but they can’t abandon the center or, given the geography of American politics, the center-right, and still hold power.

Klein doesn’t specify the kinds of campaigns and tactics that succeed for Republicans and it isn’t clear the degree to which those campaigns or tactics are markedly to the right of the average American voter. But what if these supposedly extremist Republicans are competing on center and center-left territory?

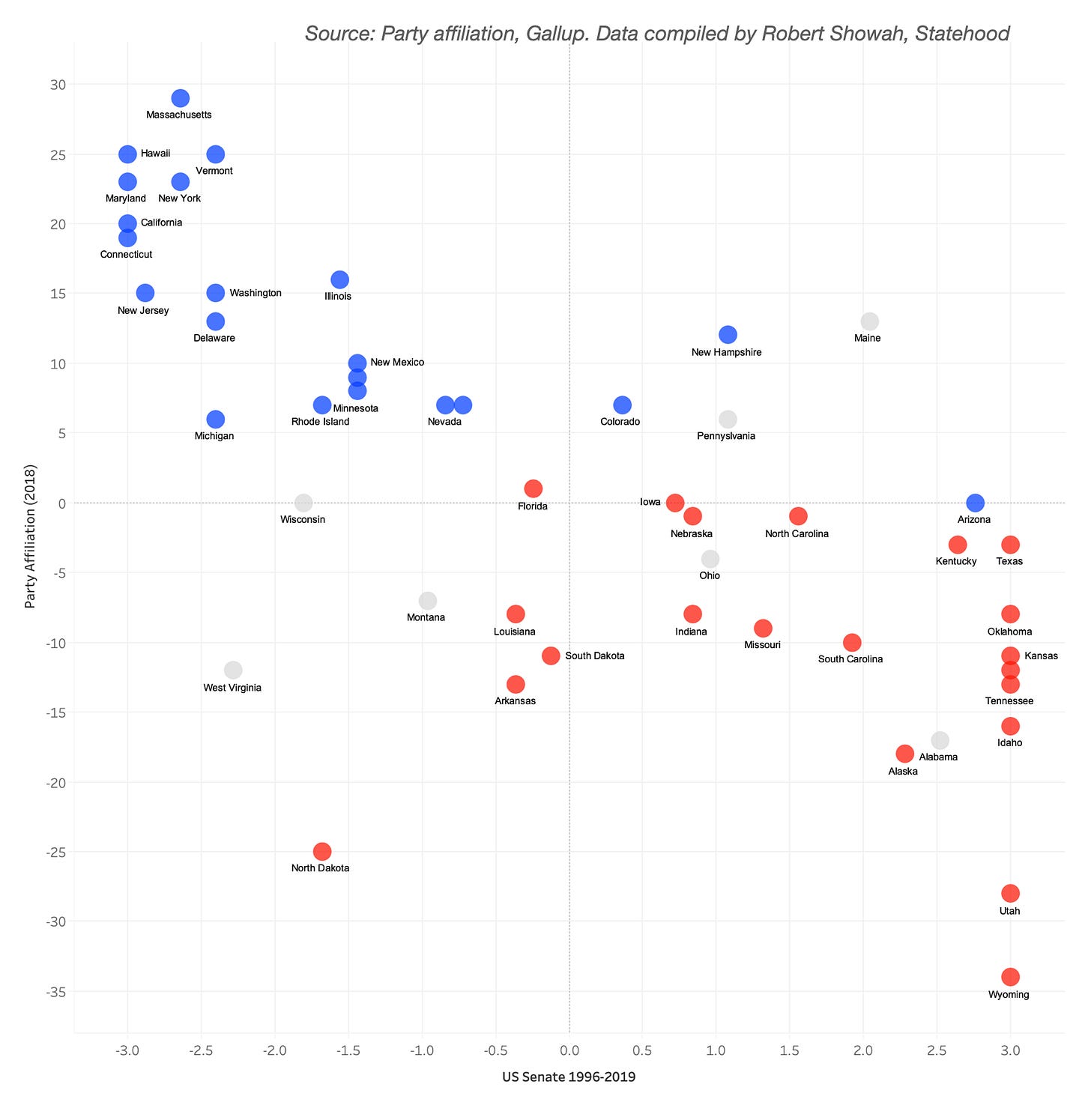

One way we can find out is by looking at where Republicans are winning. In states where residents are equally or more likely to affiliate with Republicans, according to Gallup, Senate Democrats hold six seats. In states where residents are equally or more likely to affiliate with Democrats, Senate Republicans hold 11 seats.

What about winning over Democrats in competitive states where party affiliation is within five points? In recent elections, eight Republican senators have been (re)elected with above-average percentages of the Democratic vote, including Mitch McConnell in Kentucky (17 percent), the late John McCain in Arizona (16 percent), Rand Paul in Kentucky (15 percent), Chuck Grassley in Iowa (18 percent), Rob Portman in Ohio (18 percent), Johnny Isakson in Georgia (12 percent), Marco Rubio in Florida (12 percent), and Pat Toomey in Pennsylvania (12 percent). In four of those states, party affiliation is within a margin of 1 point.

And within the decade, Republicans have flipped seats in blue states that had more frequently elected Democrats than Republicans to the Senate including two seats each in North Dakota and Arkansas, and one seat each in South Dakota and Montana.

Constituencies less likely to vote for recent Republican presidential candidates have also voted for Senate Republicans. In 2016, Isakson was reelected in Georgia with 18 percent of the black vote, doubling Trump’s 9 percent share in the state. In 2018, Republican Rick Scott unseated Democrat Bill Nelson in Florida by one-tenth of 1 percent, or 10,000 votes out of 8.1 million cast. Scott did it with 45 percent of the Latino vote, to Trump’s 35 percent in the state. In 2020, David Perdue in Georgia, John Cornyn in Texas and Mitch McConnell all increased their share of the black vote by four and seven points from six years ago.

When Nate Silver and others refer to Democrats’ status in the Senate as a structural advantage in a structure that hasn’t changed for 240 years, it brazenly redirects blame for a party’s failures at anyone and anything but the party itself. It’s a lot like wondering why a murder victim got themselves murdered. It misses the point. The only disadvantage the Democratic party is at is with itself. Democrats cannot go on ceding enormous shares of the 68 seats in the U.S. Senate represented by suburban and rural states while banking on a narrow urban constituency to deliver commanding majorities in the Senate as well as the House. The center in America is closer to Williamson County, Texas, Henrico County, Virginia and Maricopa County, Arizona than it is Brooklyn, New York or Washington, D.C.

In America, in federal elections, multi-majorities rule because we are a nation built on a skepticism of centralized authority. The people are depolarizing to the suburbs. Whether Democrats join them and depolarize their political coalition will determine the longer-term strength of party.