Did Federalism or the Feds Fail New Orleans?

Twenty years after Hurricane Katrina, disaster responses have improved but there are lessons to reflect on about divided power.

Hurricane Katrina was one of those unforgettable news events, seared in memory like 9/11. The images still linger: a drowned city from the air, families stranded outside the Superdome in the August heat, bodies floating in streets where life had ended overnight. Reporters like Anderson Cooper and Shepard Smith did some of the best work of their careers on that story. Aaron Brown’s measured coverage for CNN stood out most to me, just as it had on 9/11, letting the story largely speak for itself. His work inspired me to write. Back then, I wondered why anyone would live in what looked like a bowl at the edge of the Gulf of Mexico. Since then, I’ve visited well over a dozen times and cannot imagine life without going back again and again.

New Orleans is a gumbo — distinct subcultures stewing together in a shared roux. It is a majority-Black and largely Catholic city with a large Vietnamese community. Everything is weathered yet airbrushed into a colorful oblivion. The dead are buried in tombs. Drinking in the streets is legal. Flash parades are an acceptable excuse for being late to work. You can erect a makeshift Tiki bar on a street corner during Jazz Fest and be ignored by police. Solo brass musicians can be distantly heard at twilight on a remote street corner. In spring and summer, a thin donut glaze of sweat coats your arms and face. You’re uncomfortable, but there’s too much life around to dwell on the humidity. It’s a city for old souls that is young at heart. Though New Orleanians are resilient — and they are — they’re also exhausted from having to be resilient amid entrenched corruption, weak infrastructure, and high crime. A running historical theme of the city is making do with little: shotgun houses built for economy in the 19th century, or red beans and rice and chicory coffee stretching budgets. What New Orleans lacks in efficiency, it makes up for in a joyful soul that no other American city has.

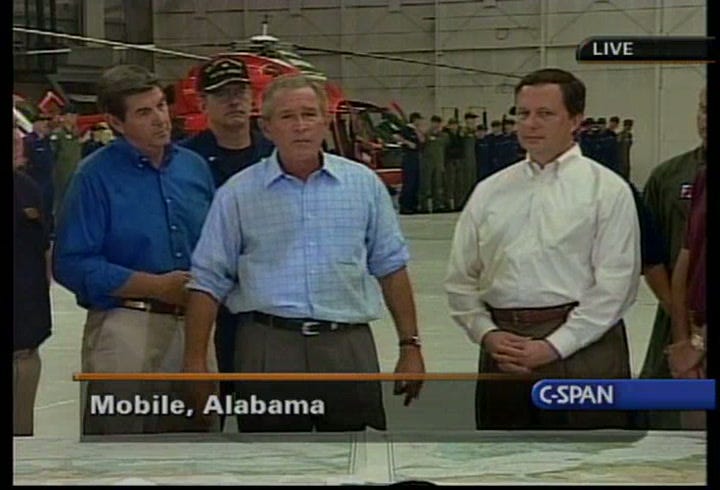

Two decades later, Katrina remains less a story of a powerful storm than of political and institutional failure. A levee system riddled with flaws collapsed, turning disaster into catastrophe. Local leaders hesitated to evacuate, state leaders resisted federal coordination, and FEMA proved hollowed out by years of neglect in favor of counterterrorism. The chaos that followed raised a lasting question: did federalism fail New Orleans, or did the federal government itself fail?

Three failures stood out: a late and incomplete evacuation, a governor unwilling to cede command of the National Guard, and a federal disaster agency overwhelmed from the start. My aim here is to no rely on hindsight because tough decisions were being made with the information available at the time — including the unexpected pivot of Katrina from the Florida panhandle westward toward the Louisiana-Mississippi border.

Mayor Ray Nagin waited until the weekend before landfall to order a mandatory evacuation, leaving little time to move residents without cars. Rows of flooded school buses became an enduring symbol. Yet false alarms had plagued the Gulf for decades, and evacuating a city is costly and politically fraught. His hesitation was less negligence than a gamble gone wrong.

At the state level, Governor Kathleen Blanco never handed control of Louisiana’s Guard to federal authorities, despite White House pressure. She feared that once federalized, Guard troops would be bound by restrictions like the Posse Comitatus Act, limiting their ability to police the city amid looting and disorder. Instead, New Orleans was aided by a patchwork: Louisiana Guard units under her command, reinforcements from other states under Louisiana’s authority, and active-duty federal troops reporting separately to the Pentagon. Aid arrived, but through overlapping chains of command that slowed and confused the response.

Mississippi’s governor, Haley Barbour, made the opposite calculation. He never ceded legal control of his Guard either, but his long-standing ties to Bush meant coordination came quickly and without public friction. Federal troops and out-of-state Guard reinforcements integrated more smoothly, and the recovery there, while still punishing, carried less of the paralyzing blame game that defined Louisiana’s experience.

Then there was FEMA. The agency’s collapse was the clearest institutional failure. After being folded into the Department of Homeland Security, FEMA’s natural-disaster mission had been subordinated to counterterrorism. When Katrina struck, it lacked the staff and logistical muscle to coordinate relief. Supplies stalled, communications broke down, and even once authority questions were resolved, FEMA couldn’t deliver.

So did federalism fail, or the feds? One way to reframe the question is to ask whether the critical decisions Nagin and Blanco faced should have fallen at President Bush’s feet. What if the federal government had taken control from the outset—would it have mattered?

The counterfactual is tempting: imagine Bush ordering a mandatory evacuation and federalizing the Guard on Sunday before landfall. In theory, that solved the two biggest bottlenecks. But in practice, Washington had no more capacity to move hundreds of thousands without cars than New Orleans did. Without buses, drivers, or staging sites, the problem remained the same. Even had Bush seized the Guard, the reality was grim. Louisiana’s units were depleted by overseas deployments and scattered across the state. Coordination with active-duty forces might have looked smoother on paper, but flooded streets, broken communications, and the sheer scale of collapse would have slowed them all the same. Federal command wouldn’t have made helicopters fly faster or conjured high-water vehicles.

The real failure wasn’t authority but capacity. Bush could have shouldered more political risk by overriding Blanco and Nagin, but it’s doubtful the feds could have delivered much better in those first four or five days. FEMA wasn’t ready, the military wasn’t pre-positioned, and roads were gone.

Yet even these failures — the late evacuation, the tug-of-war over Guard authority, FEMA’s collapse — miss the ultimate one: the levees. Postmortems found that many collapsed below their design thresholds. This wasn’t just a storm too strong to contain; it was preventable. Had the levees held, New Orleans still would have flooded, but not eighty percent of it. A smaller footprint would have meant fewer stranded residents, clearer supply routes, and an easier job for Guard units and FEMA. The federal failure didn’t begin after landfall; it was decades in the making, when Washington failed to invest in adequate defenses.

In the years since, law and habit have shifted. FEMA’s authority was expanded, clarifying lines of responsibility. The dual-status commander system was institutionalized, allowing Guard and active-duty troops to operate under one chain without forcing governors to surrender authority — a system that worked well in disasters like Hurricanes Sandy and Harvey last decade. Governors now routinely request disaster declarations before storms make landfall, letting FEMA pre-position supplies. Mayors are quicker to order evacuations and plan transport for those without cars. Political leaders tend to over-prepare rather than risk hesitation.

One refrain after Katrina was: “How could such a failure happen in the United States, a country with the wealth it has?” The critique assumes that tangible resources and money can resolve complex crises. In reality, Katrina showed that capacity, planning, and competence matter more than money in the moment. Nagin, for his part, though his frustration was understandable, all but called for centralization in post-disaster interviews, implying that a singular chain of command was the only way through the Blanco-Bush impasse. But that argument overlooks how the feds are no less susceptible to incompetence than subnational authorities but also the precedent that such an approach sets long-term for the country.

In New Orleans, federalism didn’t fail. Leaders did. And citizens should be wary of conflating impediments to centralization as failures of the system. Emergencies are precisely when divided power most needs protecting. That doesn’t preclude better coordination — but if we don’t recommit to preserving divided authority, there will be figures who come along eager to test it.