Tear Down the Presidents

The current moment demands patriotic Americans to reckon with the aggrandizement of the presidency in the land of no kings.

Author’s Note: This is a post I had been wanting to write for some time and Independence Day seemed as good a date as any to drop it. This also comes days after the Supreme Court delivered mixed opinions on presidential power; the Loper decision that curtailed the autonomy of executive agencies and the Trump case that affords to the president broader immunity from prosecution. These cases underscore the point that it isn’t any one president that is the issue — an angle the press gets far too fixated on. Upon developments like these, the instinct of the people, the press and the elected should be scrutinize the office and those that delegate outsize power and cultural influence to it.

I grew up on the banks of America’s origin.

A couple of miles away, the first English settlement was established. A few miles further, the capital of the British Virginia Colony where George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and others began their careers and later plotted rebellion against their monarch. Sixty miles west, Monument Avenue in Richmond once displayed statues of Confederate figures like Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee, men who co-opted the words of the Founders to justify slavery.

In 2020, after years of debate about whether the removal of Confederate statues would represent erasure or repudiation, that year’s riots mounted pressure on leaders to remove them or leave them to be further defaced by activists. By the end of the summer, the Confederates of Monument Avenue, along with some 160 other Confederate statues across the South, were removed. Overnight, the conversation around what these statues represent changed. But it prompted a deeper question: Why do any of these exist in the land of no masters and no kings?

I had passed by the Confederates countless times living in Richmond; they were mere blocks from me. Even as a historically curious and politically literate person, I viewed them as many Richmonders and Virginians did—as markers of history and as architectural accents to my neighborhood, the Fan, a grid of charming 19th and 20th-century townhomes.

The removal of the Confederates for years had merit. The most compelling argument was straightforward: statues of people who fought for slavery at best belong in museums and not openly placed below the glistening sunsets that fall on Monument Avenue. Commentators seemed more occupied with the impetus for their removal, who was advocating for it, what it would represent, and whether removal accomplished anything meaningful. To some, axing the Confederates was a socially divisive sideshow, a distraction by zealous social justice activists whose vandalism wasn’t doing anything of material substance to address forms of racial injustice. To others, opposition to removal wasn’t an endorsement of what Confederates represented but a resistance to the broader ideology of the activists. Some activists opaquely pitched removal as a step toward racial justice, whereas others framed the Confederates and the Founders with little distinction. Opposers to removal didn’t know what change they were going to get.

Despite the clear moral schism, a commonality between the statues of the Confederates and the Founders is that each was erected if not primarily as tributes to the men themselves, then to the causes for which they fought, each a form of resistance to authority, each coinciding with its own tarnished associations. It’s clear by now that the developments of America’s social and political order have shifted toward removing the Confederate from public grounds. But what about the Founders, specifically the presidents?

Given the alarming power the presidency has amassed since the construction of these statues, the misplaced expectations hoisted upon it, the gross abuses of power across administrations, and the micromanagement of American business and civilian life that far exceeds what King George III could have dreamed of—given all of this, it’s fair to ask whether our habit of aggrandizing presidents needs to end.

Washington was famous for his humility and initial reluctance to accept the presidency when elected. Thomas Jefferson, too, opposed monuments devoted to any of the nation’s founders as it resembled the monarchism from which they rebelled. John Adams was not a fan of having a monument erected in his honor writing in 1819, nearly twenty years after his one-term ended as president:

“Monuments will never be erected to me . . . romances will never be written, nor flattering orations spoken, to transmit me to posterity in brilliant colors,”

The presidency today wields far more power and cultural influence than the Founders ever envisioned. This expansion of executive power—through mechanisms like executive orders, emergency powers, and foreign policy dominance—has fundamentally altered the balance of the federal government, often at the expense of Congressional authority, public transparency, the States and consequently the people.

Presidents have used executive orders and actions to implement policies without Congressional approval and signing statements to interpret legislation, undermining Congressional authority. War powers have shifted, with presidents engaging in military actions without formal declarations of war. Emergency powers invoked to address crises grant broad unilateral authority. The growth of the administrative state has increased presidential control over regulations, while executive privilege reduces transparency. Foreign policy dominance has expanded, giving presidents greater control over diplomacy and military operations. Additionally, the influence over the federal budget, expanded surveillance, and intelligence capabilities have further increased executive power. National security directives and the delegation of broad powers by Congress have also enhanced the executive branch, resulting in a presidency far more powerful than the Founders intended.

Then there’s the cultural influence enlarged by a political press that uniformly attributes everything from short-term economic trends to the “tone” and “mood” of the nation to the presidency—all the while warning of autocracy and decrying those who declare that “I alone can fix it”. The economy writ-large is commonly attributed to presidents in the possessive, a Dear Leader pulling the levers of the economy toward glorious prosperity with his muscular strength. The language used by the president and his supposed watchdogs alike—that we live “under” the president, that the president “runs” the country when he “comes to power”—sounds despotic. The state of the union addresses, forums, and debates are spectacles. The president is asked what he will do about matters beyond his authority and political capital. He is incentivized to lie instead of setting comparatively lower but realistic expectations because leveling with the public will be interpreted as weakness by political journalists and his opponents. The president’s opinion on matters outside of his jurisdiction is commonly solicited, and with that solicitation an expectation that he intervenes regardless of the legality or long-term implications of emboldening the office. And so it isn’t surprising in hindsight that a figure would come along who thrives in the limelight, constantly seeks attention and validation, lashes out at dissent, and enjoys power for its relevance over the ends it can achieve. As Arthur Schlesinger wrote in The Imperial Presidency, the American political system was threatened by “a conception of presidential power so spacious and peremptory as to imply a radical transformation of the traditional polity.”

Progressives need less convincing that removing the statues of presidents is, if not in keeping with American ideals, then a rejection of an outdated social order and disregard for minority populations. In at least one major case, they have a point.

The construction of Mount Rushmore involved the displacement of the Lakota Sioux tribe from land they considered sacred. But to add insult to injury, after passing the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868 to protect the lands, the federal government backtracked, allowing settlers to pour into the area after gold was discovered. Much of the gold rush ended in the late 1870s. Fifty years later, in a twist of the metaphorical knife, Mount Rushmore was carved into the Black Hills. Where progressives might theoretically advocate an alternative future paradigm that honors American ideals of equality and justice over presidents, the trouble is that for progressives, skepticism of government power is limited strictly to the police.

For the moderate squares in the commentariat, statue removal risks threatening “national unity” and a “shared history,” which have always seemed more present in the eyes of professional storytellers than laypeople. But increasingly it seems that unity—or an approximation thereof—lies in common principles that transcend the factions to which presidents belong. In practical terms, today, presidents represent uniformity, the prospect of transformational change on the thinnest of margins. In a diversifying union of states, uniformity is untenable. A quintessential centrist solution predictably federalizes or “presidentializes” a clearly divisive and hyper-regional matter by advocating for a, you guessed it, national task force to compare ourselves to other parts of the world in hopes of finding (or imposing) that elusive national consensus we hear so much about.

It’s the conservative instead that would need convincing that removing the statues is in line with American ideals. On the merits, the conservative case is simple: The Founding Fathers envisioned a republic where power resided with the people, not in the hands of a single leader. Erecting statues of presidents elevates individuals to a status akin to monarchs, fostering a form of idolatry that the Founders explicitly sought to avoid. But barriers stand in the way.

For one, pride in one’s country and a bias toward tradition to retain what already exists. Then there’s the sense, although seldom said so explicitly, that it would lend succor to the far-left. Perhaps among a smaller vocal minority of conservatives, they might defend existing statues as examples of the strongman we need today. None of these intuitions can be reversed overnight.

There’s the concern that Americans will be less historically literate without the presidents looming over them. And yet, it’s well documented that Americans’ knowledge of history and civics leaves much to be desired anyway. It may well be that their removal induces them to seek out more information about what has vanished.

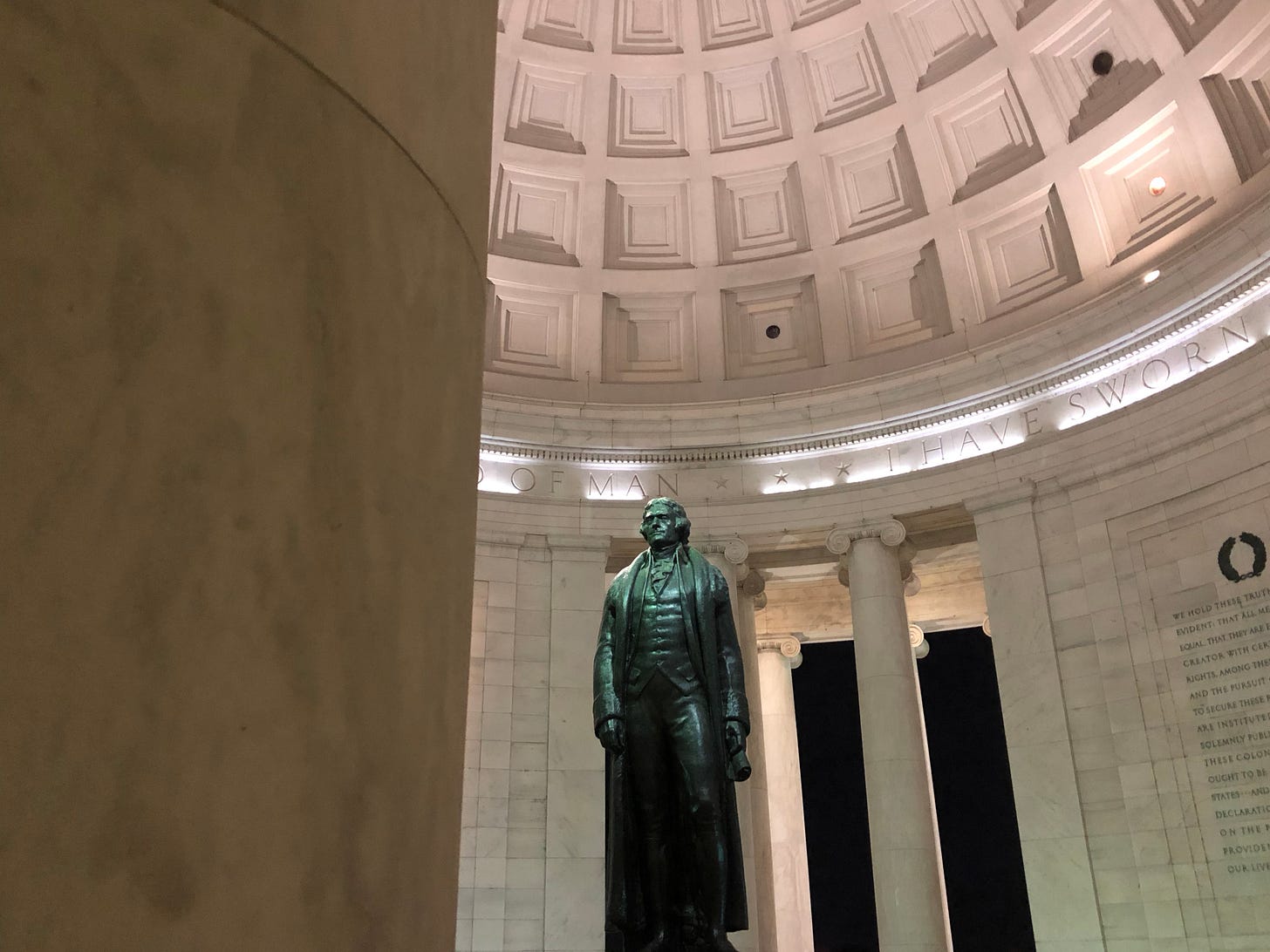

Venerating presidents, given not just the current moment but the expansion of presidential power over the last century or more, doesn’t seem obviously appropriate anymore. Serene and immense as the Lincoln Memorial is late at night, to recognize Lincoln’s contributions (and usurpations of power) need not prompt any American to regard him as Jupiter enthroned at his temple. The Lincoln Memorial can be rededicated to Union soldiers, the Jefferson Memorial to the Declaration of Independence, and our currency to other influential American figures.

In 2004, just miles from the former Capitol in Williamsburg, a local entrepreneur opened Presidents Park, a ten-acre visitor attraction in the heart of Virginia’s historic triangle featuring 20-ft busts of the presidents up to then-President George W. Bush. Six years later, as with a similar attraction in South Dakota, the park went out of business and was put up for auction. The presidents’ heads were towed to a private field in Croaker, where they continue to sink into disrepair.

The United States loses nothing without its presidents but it stands to lose a great deal by continuing to make them and the office they occupy the heart of the American story.

That Patchwork is a first-of-its-kind newsletter about democracy, economics and culture from a decentralist angle. Today, fewer people are seeking more power over American life. To preserve a pluralist democracy will mean challenging the entrenched premise that observations, ideas and solutions are best made with a federal or national interest.

Subscribe below and get a subscription for just $3/month for an entire year.

Beyond That Patchwork

I was reminded of Charles Bradley today and “Good to Be Back Home” off his 2016 album Changes. Bradley spent years as a James Brown impersonator before finding broader success later in the life with his original work. This is among the albums that defined the 2010s for me. I was set with tickets to Bradley in San Antonio, but the show was cancelled. Not long after, Bradley died in a struggle with cancer.