Texas's mail ballot drama in perspective

Reports uniformly attribute a spike in rejected mail ballots to new ID requirements and efforts to disenfranchise voters. Data and policies in other states complicate that premise.

This month Texas saw a spike in rejected mail ballots during the March primaries that reports across just about every newsroom have attributed to a new law passed last year changing the method by which mail ballots are verified from signature-matching to a requirement that voters supply a state identification number or the last four of their Social Security number. Critics say the law change is a Republican effort to systemically suppress voting with reporting generally accepting that premise. But data from other states suggest there is more at play as states with more liberal and more conservative verification standards have also seen high numbers of rejected mail ballots.

Results are incomplete but as of the week of March 15, reports indicate that of the counties comprising 85 percent of all votes cast, estimates of the number of mail ballots rejected stands at 22,898 with a mail ballot rejection rate of about 13 percent. This implies that the total number of mail ballots cast stands at an estimated 175,000. Mail ballots account for roughly 5 percent of all ballots cast. In total, 3 million votes were cast in the primary. Thus far, rejected mail ballots account for 0.76 percent of all ballots cast. Again, this is based on unofficial results and estimates.

It is worth emphasizing that the spike in rejected mail ballots in Texas is significant. In most states mail ballot rejection rates hover between 1 and 3 percent. So as much as a 13x increase should raise eyebrows and anyone concerned about the fairness and integrity of the democratic process in Texas should want to see this figure be as low as possible. As is also the case, voters identities need to be verified before their votes can be counted.

Every state, by electing officials through the democratic process, chooses who is eligible to vote by mail and the method by which a mail voter’s identity is verified.

In Texas to be eligible to vote by mail you must: be 65 years or older; be sick or disabled; be out of the county during the early voting period and election day; expecting birth within three weeks of election day; or be in jail but otherwise eligible. Until 2021, the method Texas used to verify ballots submitted by these individuals was signature-matching. Who oversees the signature-matching process and whether signature-matching is conducted manually or digitally varies by state but frequently involves verifying that the signature on the ballot matches the signature of the voter that the state has on file.

The premise on which effectively all reporting is operating is that in a state with already restrictive mail voting eligibility, Texas Republicans changed the verification method for mail ballots from signature-matching to an ID requirement in order to suppress votes, specifically Democratic votes and further the votes of nonwhite voters. The idea being that requiring an ID discourages voting, materially makes voting more difficult and will increase the number of ballots that Texas counties will have no choice but to reject under the law.

A potential vulnerability revealed in the new law before it was passed raised the prospect that for a voter’s mail ballot to count they not only would have to supply any eligible ID number but would have to supply the same ID number that the State of Texas has on file — otherwise the voter’s ballot could be flagged, and perhaps ultimately, rejected. Texas Republicans also worked into the law a means by which voters can cure a ballot with incorrect data once the county in which the voter resides notifies the voter that their ballot has been flagged.

At least one election administrator I spoke to said rejections due to “both instances were common” — meaning that rejections were both a result of applicants neglecting to enter ID information and mismatches with state records. Other reports in some of the largest counties in Texas have attributed anything from “many” to “a little more than half” to “the vast majority” of rejections to voters neglecting to submit any ID information at all. This has frequently been buried in news reports.

Mail ballots are rejected in Texas and elsewhere for a variety of reasons — because voters decline to submit curing forms after their signature has been flagged for mismatching state records, because voters neglect to properly sign their ballot or submit required identifying information, and frequently because voters do not send back their ballots by the required deadline. In other words, voters have a great deal of agency over the probability their mail ballot will be accepted — and of the vast majority of ballots cast they are accepted.

Despite this and the fact that a number of states struggle to minimize ballot rejections with various verification methods, the vast majority of the text committed to stories involving Texas election laws almost exclusively pursue sources that validate and over-index the perspective that the spike in mail ballot rejections are indicative of voter suppression, specifically to disenfranchise black and brown voters. In stark contrast, the extent to which an advocate for new ID requirements is engaged in any reportage is uniformly followed by the phrase “even though there is no widespread voter fraud in Texas.”

One of the implications of the premise reporters are operating on is the notion that the previous verification method Texas used for mail ballots and that more liberal states like California and New York still use — signature-matching — is comparatively less disruptive and less likely to adversely impact nonwhite voters. To the contrary, advocacy organizations including the ACLU have argued that signature-matching laws can disproportionately “disenfranchise marginalized populations”. Indeed, at least one analysis found that in the 2020 Florida primary, black and Hispanic voters’ ballots were rejected at roughly double the rate as white voters’ ballots, although the exact cause is unknown.

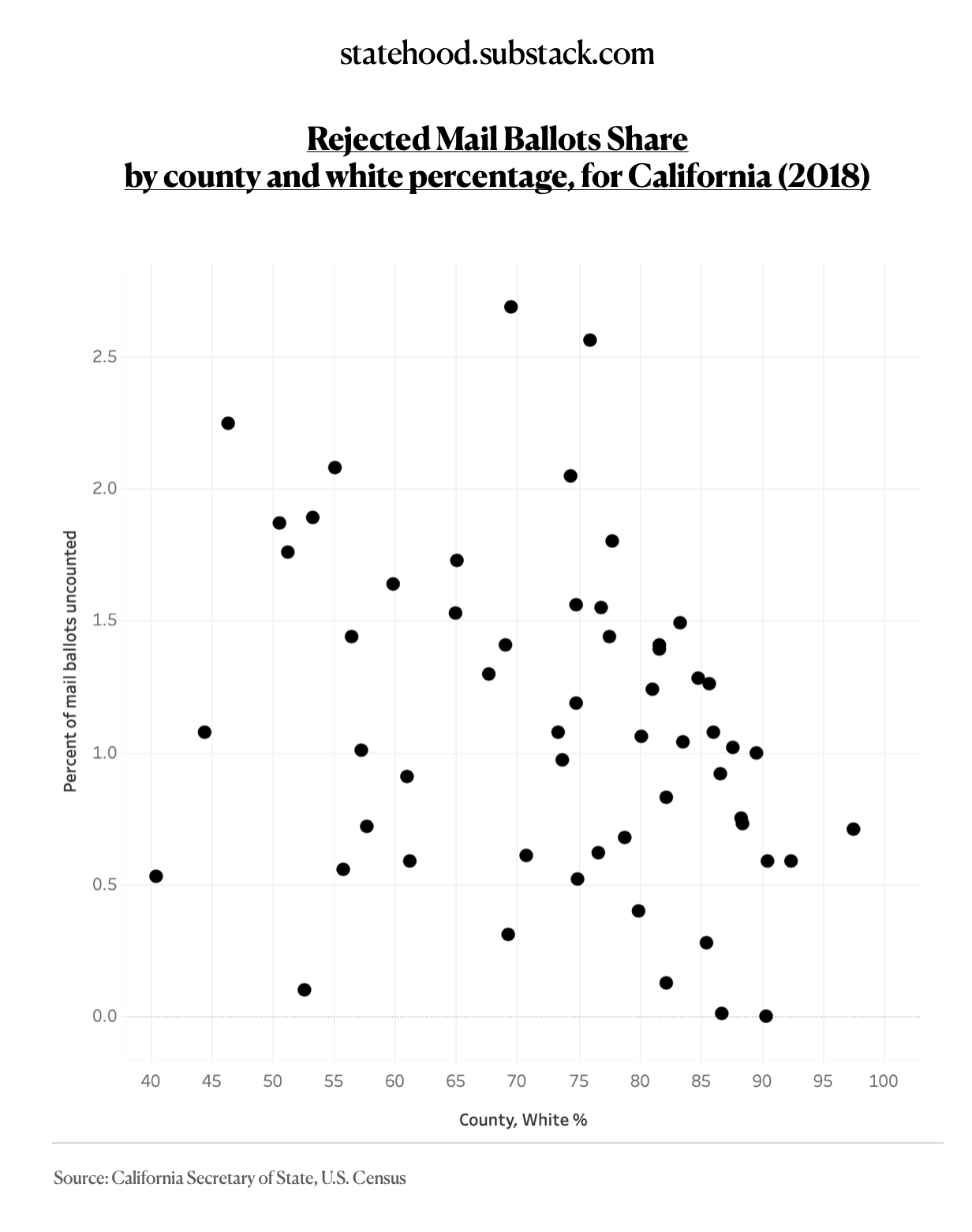

A recent New York Times' story on rejected mail ballots in Texas writes that mail ballot rejections were higher in counties with relatively lower white populations, lending credence to the premise that the law Texas Republicans passed may have seen some success in achieving its purported goal of disenfranchising nonwhite voters. Except in 2018, in California, the share of mail ballots that were rejected was, too, higher in counties with lower shares of white residents.

States employ different methods and assign different bodies of individuals to verify signatures, a process that exposes itself to the imperfect judgement of regular people seeking to discern signatures that may have changed over time and for a multitude of reasons. Suggested remedies for these discrepancies have ranged from existing policies like “curing”, which allows voters to correct issues with their ballots, often online, to more sophisticated methods involving biometric data.

Further complicating the conventional wisdom is the extent to which states with signature-matching policies can see a higher share and absolute number of rejected mail ballots, and the extent states with ID requirements have seen rejection rates on par with the union average.

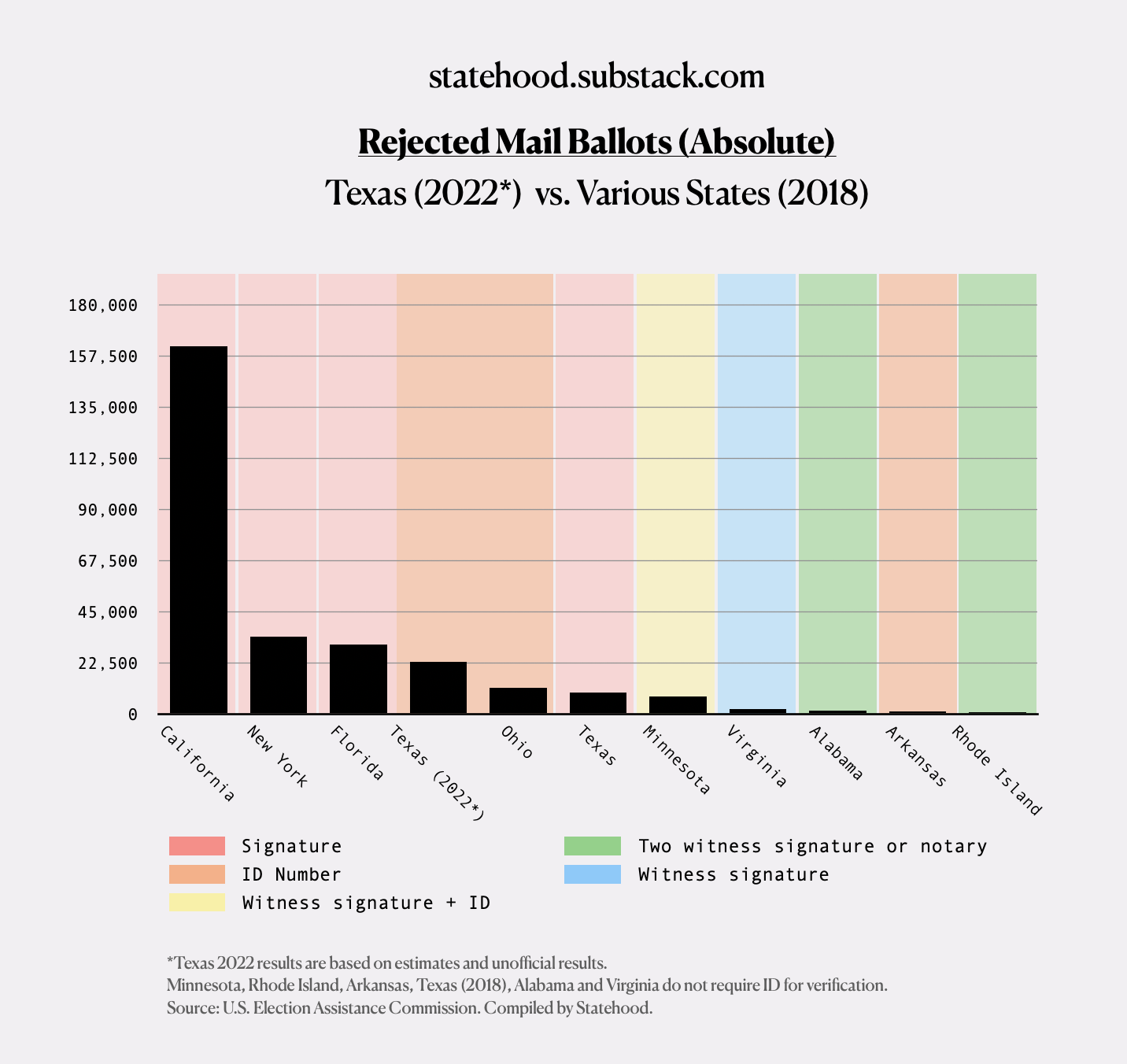

Reports have made a point to headline the number of rejected mail ballots in Texas in absolute numbers. When comparing the unofficial Texas 2022 primary figures to the general election figures during the last midterm election year, California in 2018 rejected 7 times more ballots than Texas so far has in 2022. New York followed with 34,095 rejected mail ballots, followed by Florida with 30,540 rejected ballots, and Texas at 22,898 ballots. California, New York and Florida rely on signature-matching to verify voters’ identity.

But absolute numbers alone don’t provide the most elucidating view — particularly when the mail voting eligibility standards are different across the states.

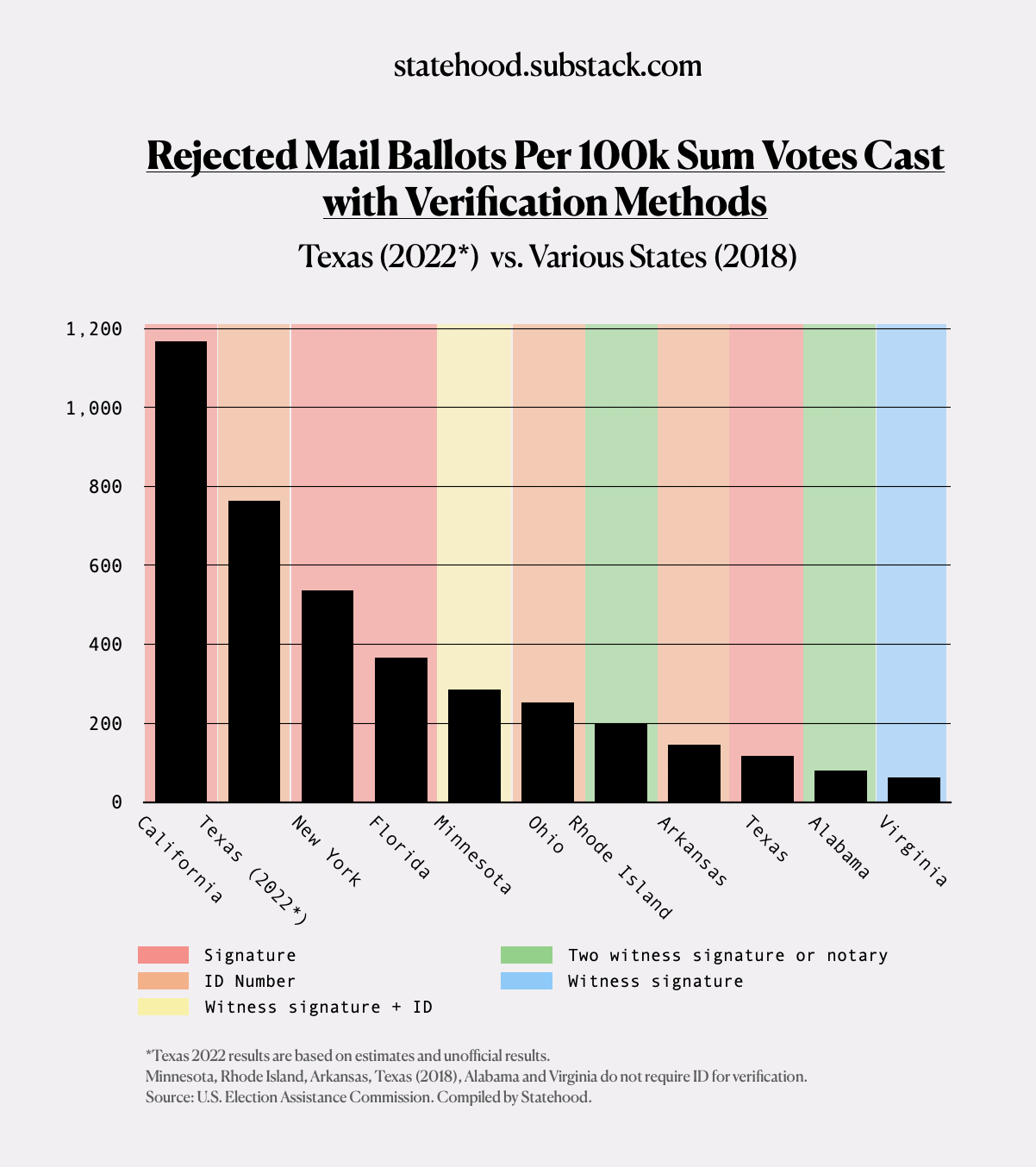

When comparing states per 100,000 ballots cast, Texas in 2022 compared to other states in 2018 ranks second highest behind only California. In 2018, California rejected 1,169 ballots for every 100,000 total ballots cast for a total of 161,660 rejected mail ballots, or a 1.95 percent mail ballot rejection rate in a state where 60 percent of all ballots are cast by mail. Texas in 2022 saw a 6.5x increase in rejected mail ballots compared to 2018 when it used signature-matching, and this year so far rejected 764 ballots for every 100,000 cast for a total of 22,898 — or 13 percent of mail ballots. Notably, states with arguably more “burdensome” verification standards like Minnesota, which requires a witness signature and an ID, saw a rejection rate much more in line with the national average. In 2018, Minnesota rejected 286 ballots per 100,000 votes cast for a mail ballot rejection rate of 1.18 percent. 24 percent of Minnesotans voted by mail in 2018. Ohio, another of the few states that require an ID saw similar numbers. Last year, Georgia had its first election under an ID-based verification process and saw a mail ballot rejection rate of 0.6% — well below the union average.

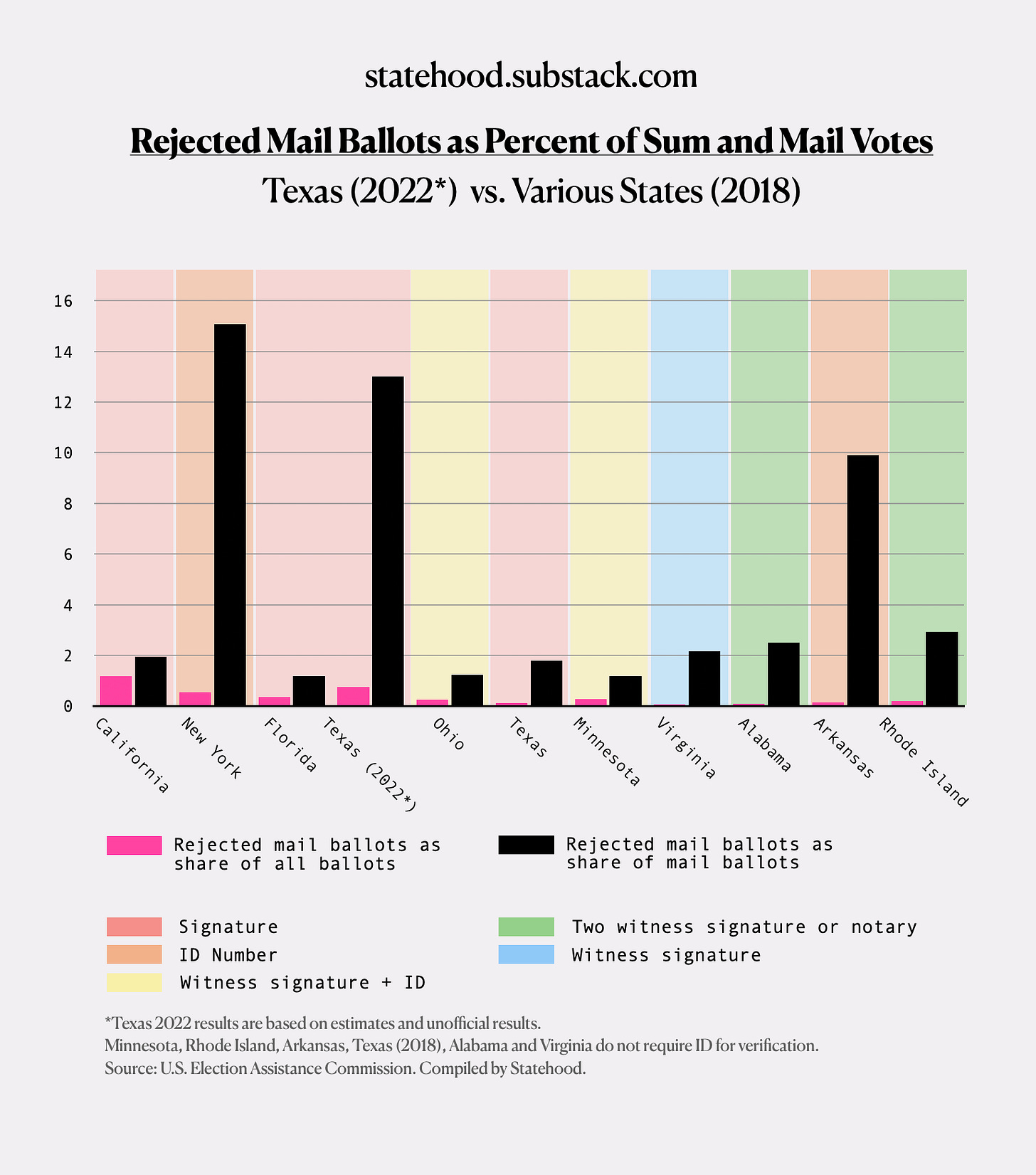

Also worth keeping in perspective is the share of mail ballots relative to the number of all ballots cast when one is surveying the election landscape. California has much looser laws governing who is eligible to vote by mail. In 2018, 60 percent of all ballots in California were cast by mail with rejected mail ballots that year making up 1.17 percent of all ballots cast. In Texas, where an estimated 6 percent of all ballots were cast by mail, rejected mail ballots so far comprise an estimated 0.76 percent of all ballots cast. In New York, a signature-matching state with tighter mail ballot eligibility laws than Texas (unlike Texas, in New York being 65 years or older is not an eligibility standard) 34,095 mail ballot were rejected for a lower total rejection rate of 0.54 percent than Texas (2022) but a slightly higher mail ballot rejection rate of 15 percent. Arkansas, a state that requires an ID, also saw an abnormally high mail ballot rejection rate of 9.9 percent but that comprised of 0.15 percent of all ballots cast.

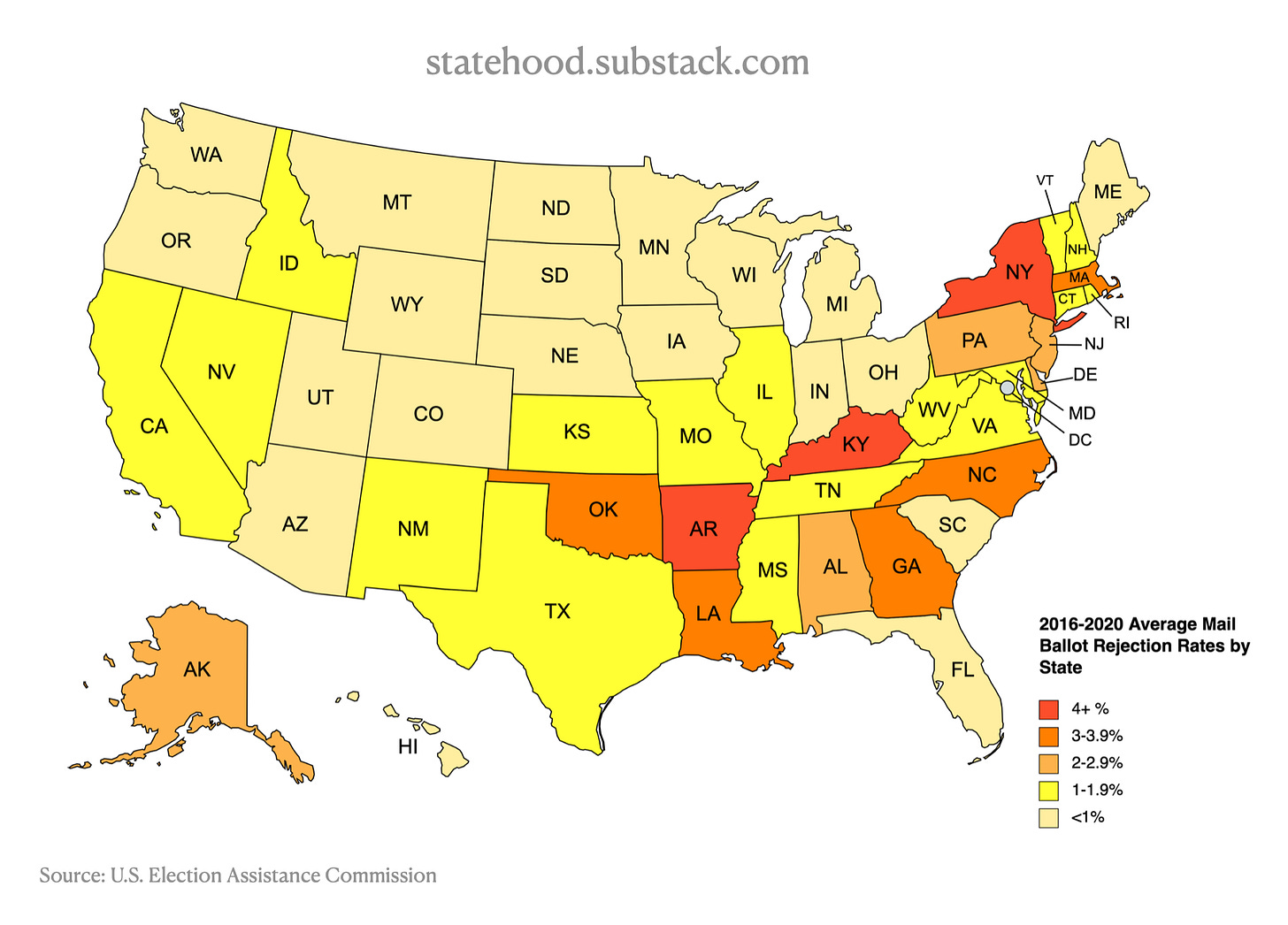

Based on the data collected by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, across the 2016, 2018 and 2020 general elections, the states with the highest average mail ballot rejection rates were New York followed by Arkansas and Kentucky. States with the lowest were Wyoming, Montana and Indiana. Missouri and Illinois hovered on either side of the union average.

There is more to learn about what happened in the Texas primary but how Texas stacks up to other states suggests that there is much more at play here than the notion that one policy over another is objectively more likely to result in an outcome with fewer rejected mail ballots. States that rely on IDs to verify voters’ identities — including those like Georgia that just made a similar switch — are largely not having issues outside the norm which could suggest that the issue in Texas is largely administrative: election workers trying to do their best are adapting to the implementation of new law. If that’s the case, it’s worth understanding why that is.

Though Texas’ elected haven’t had much to say about the spike, they need to answer for a clear vulnerability in the mail voting process that ostensibly increases the likelihood that ballots are rejected despite voters supplying identifying information. The design of ballot forms and ensuring that instructions are clear as well as ensuring that voters can complete the curing process swiftly are critical points of inquiry for understanding how to improve this process for Texas voters who strongly support ID requirements for voting.

At the same time recent stories about elections laws in Texas suffer from a bias endemic in journalism which is the agency bias. This is where the agency attributed to the elected (or the comparatively powerful) over circumstances beyond their control is exaggerated — President Biden over gas prices, or Governor Abbott or voter access — and the agency attributed to the layperson (the comparatively powerless) is effectively non-existent, and subject to forces outside their control. The irrefutable truth is that if you’re capable of exercising minimal amounts of personal agency, it’s very easy to vote in Texas and really any state in the union. But that doesn’t mean processes are flawless and so it’s important that inquiry into improving them is informed by data, evidence and representative anecdotes that take into account basic logic and countervailing observations. Just as certain Republicans have led some of their voters to believe they have little influence over the outcome of rigged elections, Democrats and many reporters covering this issue perhaps unwittingly would have Democratic-leaning voters believe the same thing.

Republican-backed election laws stemming from (but also predating) Donald Trump’s unhinged and false claims of widespread voter fraud has given a kind of license to many reporters covering these issues to, in response, embellish the adverse impact of these policies and the extent to which they are by intent or impact eroding democracy even when available evidence contradicts that premise. Part of this is because reporters believe, rightly, that greater scrutiny ought to be directed at those in power who just happen to be Republicans, but increasingly fashionable is the idea that scrutiny ought to be dictated less by claims being made and more by the faintest perception of false equivalencies between the Clearly Good Side and the Clearly Evil Side — where subordinating relevant truths and letting outrageous claims stand is acceptable based on who those claims may ostensibly “serve”. Pursing such a path on this issue has resulted in a willful perhaps even gullible display of credulity among ordinarily skeptical people who’ve accepted at face value false premises including that, for example, identification laws, limits on mail dropboxes and prohibitions on unsolicited mail ballots materially impact the electorate — all of which the available evidence refutes. False claims about widespread voter fraud are no more true by saying so.

More sobriety should be practiced when delivering these figures to audiences. Inquirers would better serve those audiences by focusing on what specific parts of the process caused a spike that other states with similar policies do not typically see. That would be a good start.