The Vibe Shift That Was Missed

Republicans had been broadening their appeal for decades. Why didn't anyone see it?

In 2016, the conventional wisdom held that a coalition capable of delivering a Republican to the White House was implausible because of the purportedly shrinking base of the party. Few recognized that the GOP was expanding its coalition and that Donald Trump was building on gains the party had been making for decades. Why didn’t anyone see it that way?

One reason is the electoral journalism industry’s reliance on a single metric: presidential election results. Analysts often use the presidential popular vote to estimate a state’s partisan tilt relative to the nation overall. Yet the fact that Democrats and Republicans have won the national House or presidential popular vote an equal number of times since the 2000 election does not reveal much about the political strength of the parties.

In a federation of states, there is no singular nation. American governance stems from decisions made by the voters of individual states on their own terms. Non-binding national metrics are beside the point, much like the total points scored by a team throughout the NBA Finals is irrelevant to the outcome of the championship game.

Most importantly, sole reliance on presidential metrics obscures significant shifts toward Republicans over the past fifteen years, shifts that laid the groundwork for Trump’s coalition.

During Trump’s first term, these blind spots led writers such as Ezra Klein to argue that Republicans did not have to compete for the political center in the way Democrats do. Similarly, Ronald Brownstein condescendingly dismissed the Republican coalition as clinging to “preservation” in contrast to Democrats, who had built a coalition of “transformation.” Such narratives overlooked that Republicans had clear momentum in winning over the center on Democratic turf, thereby transforming the electoral landscape faster than Democrats could preserve their majorities across the union.

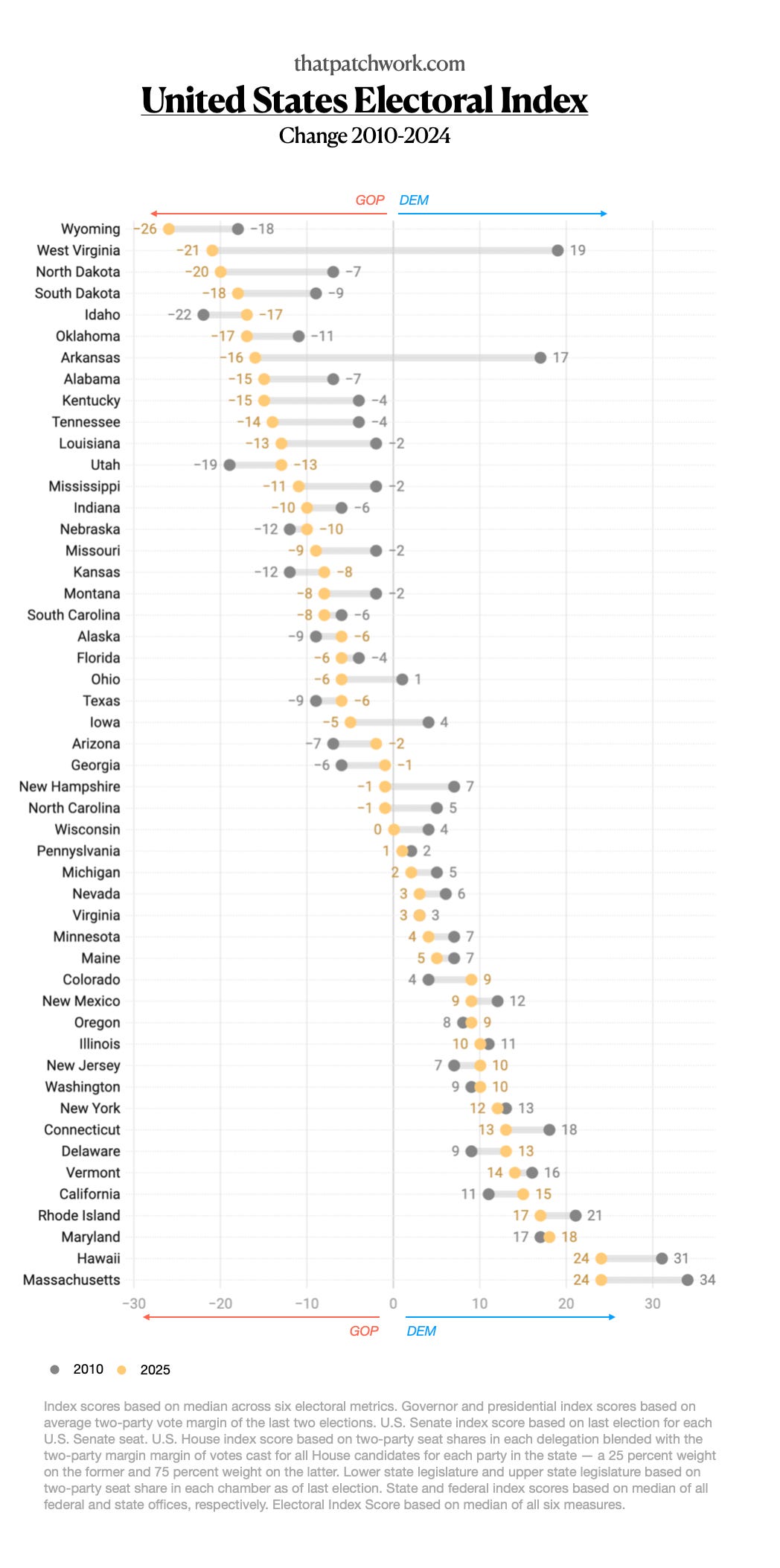

At That Patchwork, I’ve created an index to capture a more accurate portrait of each state’s partisan orientation across federal and state offices, not just presidential elections. Many consider 2016 the year that American politics entered a new chapter, but the reality is more interesting.

In 1980, Republicans broke the Democrats’ multi-decade hold on the U.S. Senate. Fourteen years later, they ended the Democrats’ gerrymandered House majority for the first time in forty years. By the late 2000s, the Democrats had managed to rebound. But after 2010, electoral shifts toward Republicans accelerated.

According to my analysis, the median state has shifted six points toward Republicans, crossing the federation’s partisan Rubicon to GOP+2 since 2010. Among the states driving that move are West Virginia, Arkansas, Ohio, Iowa, and North Carolina. It is in these formerly blue states—and others with similar political compositions—where Republicans began gaining even before Trump came along.

The 2014 elections further foreshadowed what was to come. That year, Senate Republicans picked up a modern record of nine U.S. Senate seats, including in West Virginia, South Dakota, Louisiana, and Arkansas, where they had not held seats for over a century at most. Despite their presidential voting patterns, these were blue states. Contrary to the president-centric telling of electoral history, while President Nixon’s “Southern Strategy” of the early 1970s cracked the “blue wall” of the South, Democrats held a majority of Southern U.S. House seats until the mid-1990s. Until 2010, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama legislatures were all controlled by Democrats, who also held seven Southern U.S. Senate seats and two-thirds of Midwestern seats. Today, they hold four Southern seats, in Virginia and Georgia, and about one-third of seats in the Midwest. Overall, Republican states have shifted a median of two points further toward Senate Republicans than Democratic states toward Democrats. That explains why states flipped by Senate Republicans, such as Arkansas, are now considered safe, whereas states flipped by Democrats, such as Arizona, remain competitive across multiple offices.

In state legislatures, the shift is more profound. In 2010, Republicans controlled thirty-seven of the ninety-nine state legislative chambers. Today they control fifty-nine. The median upper legislative chamber and lower legislative chamber have swung fourteen and ten points toward Republicans, respectively. For governor, six Republican-leaning states have shifted toward Democrats, but twice as many Democratic-leaning states have shifted toward Republicans over the same period.

State partisan identities are often more nuanced than presidential elections suggest. Take New Hampshire, which has voted for Democratic presidential nominees since 2008 and has swung fifteen points toward Senate Democrats. Yet at the state level, it has moved sixteen points toward Republicans, making the Granite State a GOP+1 state overall with distinct preferences for federal versus state representation.

Mainstream electoral analysis often assumes the status quo will persist, treating deviations as anomalies. This bias fueled myths such as the “permanent Democratic majority” and sour grapes among some electoral journalists and progressives of a rigged system favoring Republicans. Overemphasis on presidential politics, mirroring the national Democratic Party’s reliance on such elections, overshadowed what was happening in the states.

While presidential and Senate preferences are increasingly aligned, I find growing partisan divergence between state and federal offices. In 2008, twenty-five states had a five-point or greater gap in partisan preference between the two levels of government; today, forty do.

That such strides by Republicans have only resulted in a tenuous lead at the federal level is a testament to the breadth and durability of the Democratic Party’s once-sprawling coalition. In the states, the GOP is leading by a wider margin, but nothing is certain. Polarization will ebb as the parties realign themselves but it’s clear Republicans have made American politics more competitive than it was for much of the twentieth century. That deserves attention over the imperial presidency analysts have aggrandized to the detriment of civic discourse and electoral analysis broadly.

Every year, Americans are casting ballots of equal or greater consequence than a vote for president and, with that, directing the course of their state and the union broadly. If one is not paying attention to the states, one is simply not paying attention.

The Republican "advance" is rooted less in policy and more in culture war issues. The Identity groups in the Democratic Party bring some passion and a solid floor, but the ceiling is low. The GOP leverages that reality to their advantage. The Trans-gender attack ads vs. Harris this last election were a powerful example.

This is awesome work. For me, the phenomenon of New Hampshire shows such an importance for advocating for local control. As federalization occurs, states can be misrepresented on a national scale, even if party ID remains the same.