What Newsrooms Miss About the Virginia Election

Media reliance on presidential data obscure insights into Spanberger's big win and misrepresent states' partisan orientation.

Last week’s elections were an unambiguously good night for Virginia Democrats, at least relative to the last four years. In the erratic, pendulum-swing era of federal politics, the left held executive branch seats in Virginia and New Jersey by wider-than-expected margins—and, judging from other statewide contests, saw large swings to their advantage.

To illustrate how strong the results were for Virginia Dems, newsrooms across the country universally compared the 2025 Virginia gubernatorial (and New Jersey elections) to the 2024 presidential results. This practice—treating presidential outcomes as a baseline—is now standard among election analysts, justified on two grounds: (a) presidential elections draw higher turnout, providing what’s assumed to be a more accurate reflection of a state’s partisan balance; and (b) polarization has so closely aligned presidential and state-level voting patterns that presidential data operate as good enough proxies for understanding non-presidential contests.

Meanwhile, I feel slightly insane for having to argue the basic point that elections should be compared to like elections—governors to governors, presidents to presidents, and so on. Why? Because (a) the data differ significantly, and (b) the media—yes, “the media,” and the generalization is justified here—by using presidential results as the default frame, aggrandize the presidency in an era of overreach, condition voters to a false binary and a two-dimensional, president-centric conception of democratic federalism, and obscure the local issues that actually define governance. (It’s no coincidence that New York City voters last week rejected a proposal to move mayoral races to coincide with presidential years.)

Presidential elections are not governor elections and governor elections are not presidential elections.

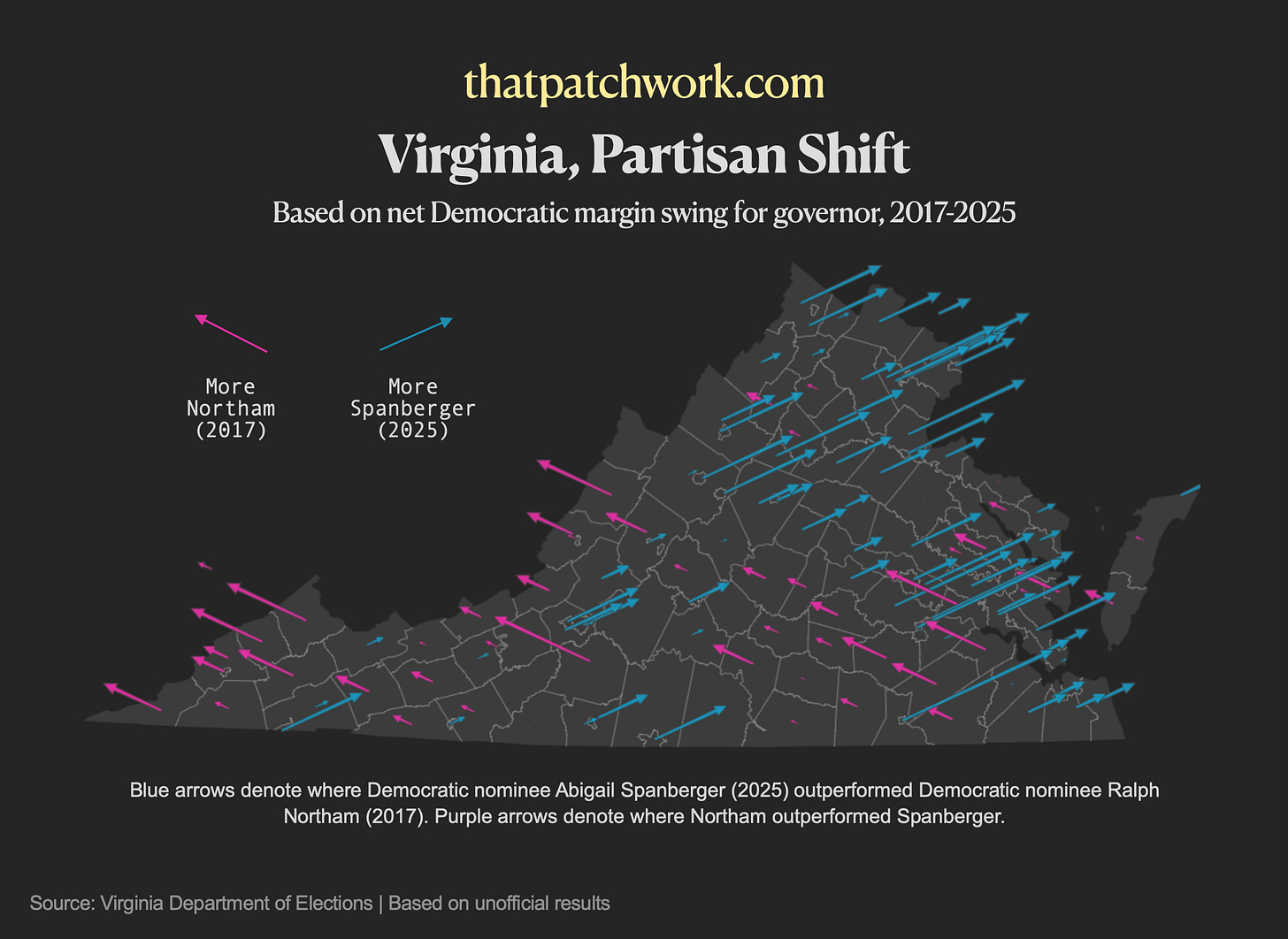

The 2025 Virginia gubernatorial results — at least the unofficial ones we have here — tell a different story from the presidential comparisons dominating headlines. Virginia moved roughly two points more toward Democrats in 2025 from 2021 than it did toward Republicans in 2021 from 2017. In 2021, the median county swung 10.1 points toward Glenn Youngkin, giving Republicans a narrow commonwealthwide win. Four years later, that same median county swung back 12.4 points toward Democrats, producing a 15-point commonwealthwide victory for Abigail Spanberger—the largest Democratic margin in modern Virginia history.

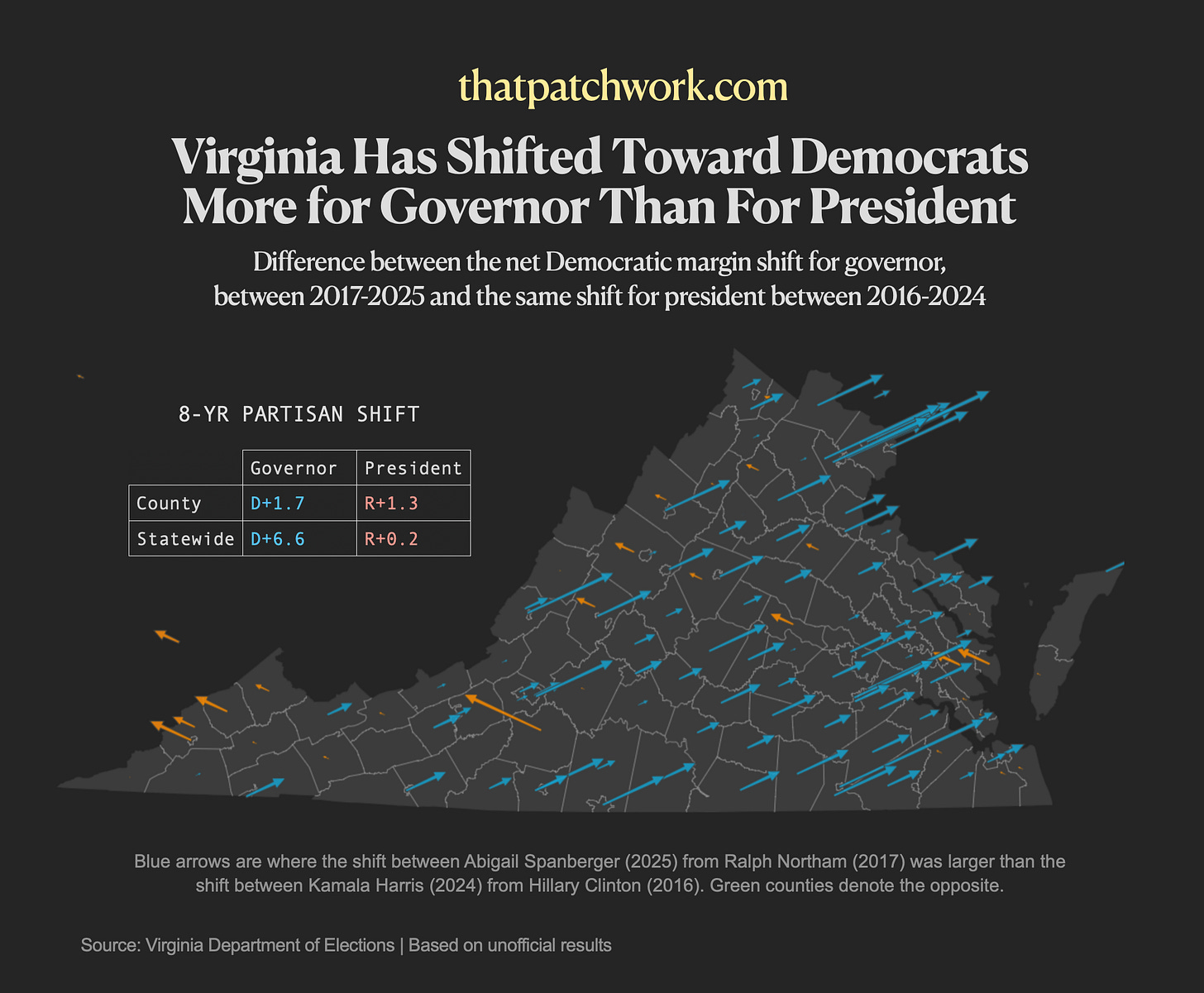

Over the past eight years—three presidential elections and three gubernatorial contests—Virginia has ever-so-slightly nudged rightward for president but meaningfully leftward for governor. The median county shifted 4.7 points toward the Republican for president since 2016, while the commonwealth overall barely moved at just 0.2 points. For governor, the same median county moved 1.7 points toward the Democrat, but the commonwealthwide margin improved by 6.6 points—evidence that Virginia’s Democratic gains are concentrated in its most populous counties. That the presidential vote has become less elastic, while gubernatorial races remain more sensitive it seems to shifts in persuasion and turnout. In other words, the swing toward Spanberger was far larger than comparisons to 2024 presidential results would suggest.

Spanberger’s map also looked different. Nearly every county swung in her direction — just as nearly every county had swung toward Youngkin in his — but she notably underperformed Ralph Northam in some areas, her Democratic predecessor who won by 8 points commonwealthwide. Northam outperformed her in western Virginia and parts of Hampton Roads, but Spanberger outperformed him significantly across Northern Virginia, the northern Tidewater, and central and south-central Virginia winning 70 percent across ten Northern Virginia localities—up from Northam’s 66 percent—and notably 50.4 percent everywhere else, making Spanberger the first Democrat since at least McAuliffe in 2013 to win a collective majority of the vote everywhere outside of NoVA.

Conversely, in the House of Delegates, Democrats picked up 13 seats bringing their majority to 64 seats on 58 percent of the commonwealthwide vote, the largest House majority for the party since the mid-1980s. Democrats controlled the House during redistricting, giving Republicans a taste of their own gerrymandering medicine.

Spanberger’s shattering of the Democratic ceiling — across any office — could be chalked up to how little regard Virginians have for the current president and the false premise that the president is responsible for the federal government shutdown disproportionately affecting those who reside in northern Virginia. The shutdown itself combined with Spanberger’s strong campaign on local issues, a lackluster opponent without messaging discipline, non-consecutive term limits on incumbent governors, plus being a level-headed and likable moderate all coalesced to work in Spanberger’s favor.

In some ways it seems Democrats have reached their electoral ceiling in the commonwealth. In two years, the narrowly divided Virginia Senate where Democrats hold a 21-19 seat majority will be up for re-election. In 2019, Democrats regained the majority by flipping 2 seats in what was Republican gerrymandered map. Now, with a map Democrats drew in 2021, it remains to be seen if the party can rekindle the magic of this year.

Spanberger’s victory wasn’t proof of a realignment so much as a recalibration: Virginians rewarding steadiness, moderation, and functionality in a moment defined by fatigue with national dysfunction. Whether Democrats can sustain that balance—governing pragmatically while keeping their coalition energized—will determine if this year marks a peak or simply a pause in Virginia’s long, uneven evolution.

Be sure to subscribe below to get That Patchwork’s 2026 Electoral Index — the only electoral index that measures partisan composition at the state and federal levels.