Would A Reapportioned Federal Senate Look Much Different?

We'll never know for sure, but there's reason to believe it would not.

Last week, Wyoming held its primaries to determine who its nominees will be for a number of federal and state offices. And as is frequently the case when the Equality State makes the news, there’s a certain kind of person on Twitter who doesn’t spare the opportunity to lament the state’s roughly 100,000 voters, it’s two federal senators, or for that matters its entire existence within the union. All of this invariably leads to a slapfight over the fairness of the federal Senate.

This was reflected in New York Times’ journalist Michael Powell rather benignly tweeting the following in response to criticism of the Senate during the Wyoming primaries:

“Not quite clear at the shock & dismay at # of Senators in small population states. That's the constitutional structure. Congress a different picture. NY has 26 congressman, 18 Dems. California has 53, of which 42 are Dems. Wyoming? It has one.”

By “Congress” Powell was referring to the House whose apportionment is more proportionate to the Senate. The industry in which Powell works compounded by the leftward tilt of the political Twitter userbase meant that Powell’s tweet was summarily ratioed. All of this reignites the Extraordinarily Online debate over the structure of the U.S. Senate — a conversation that only exists among hyper-partisan journalists and Ivy League academics upset with Republican gains in a chamber Democrats dominated for most of the last century. Now, Republicans stand to gain (though not nearly to the same extent) from the same structural forces that benefited Democrats and allowed the party to bludgeon the Senate GOP into 26 consecutive years of minority status.

Now, I’ve written about the critiques of the Senate and why they don’t hold up here, here, here, here and here, and so I’m not going to rehash every bit of it here.

But to briefly recap most of the critiques of the Senate coming from American political commentators and academics are primarily politically-motivated. Republican gains of blue Senate seats in lower population and more rural states have chipped away at the Democratic party’s historic advantage in the chamber at a time when the party’s policy ambitions and it’s very online technocratic supporters have grown. The most common case against the Senate is that polarization has accentuated disparities between seats and votes earned (nationally) in a way that was obscured through much of American history because party coalitions were different. The idea is that now that rural voters in certain states have turned on Democrats, a reapportionment of the Senate would rebalance the supposedly biased chamber.

The first problem with this critique is that for the overwhelming majority of the time Democrats controlled the Senate over the last century they did so by seat margins disproportionately larger than their House and presidential margin — inequities that had they not existed would have altered or doomed the path of landmark pieces of Democratic legislation.

It’s also worth mentioning that ironically over this period Republicans have been ascendent in the Senate since their 1994 wave, Democrats have had a harder time holding the House than the Senate. All of this undercuts the urgency with which reform is supposedly needed.

The second problem with this critique is that it overstates the role rural and lower population states are playing in the perceived bias of the Senate against Democrats for two reasons. The parties split representation evenly between the twelve least populous states creating a wash in a proportional Senate. When it comes to the yet smaller share of rural and low-population states, while those have broken for Republicans in the recent decade, it’s the midsize states where Republicans’ advantage lies. Further Democrats’ margin in the most populous states, while larger, aren’t so large that they foreclose a Republican getting elected. The third problem is that there’s a fairly good chance that the partisan composition of a proportional Senate may not look so different from the existing Senate.

Before we move on to the hypothetical it’s worth briefly mentioning that Senate reapportionment is some seriously pie-in-the-sky stuff. There’s little polling on this but the reputable polling that does exist indicates reforming the Senate to be unpopular. When asked whether the Senate would grant more senators to more populous states, 62 percent of likely voters opposed and 24 percent supported; that’s not an enormous national majority but mapped onto the federated electorate it’s far outside the window of probability right now.

Equal suffrage among the states in the Senate is protected in three separate sections of the federal constitution: in Article I Section 2, in Article V, and in the 17th Amendment. A constitutional amendment to reapportion the Senate would effectively ask state representatives of most of the union’s states, not just the lowest population states, to dilute the influence of their voters’ voices in Congress not to mention the amendment would require an overwhelming majority of popular support.

There are three distincts features of the existing Senate:

Equal suffrage. The proportional representation in the House is balanced with equal suffrage in the Senate in order to balance representation and check the power of larger, better-resourced and often wealthier states from directing federal policy.

Staggered elections. A third of the chamber is up re-election every two years which along with reducing the probability that one faction uniformly takes power also serves the purpose of distributing the electoral risk factions face, especially majority parties, who may not stand to lose as many seats as they could in a backlash.

Longer terms. Senators serve terms of six years which insulates senators more than presidents and House members from being excessively influenced by the momentary whims of the public but also the more radical elements of intraparty factions.

In the following scenarios, we’re eliminating equal suffrage and tweaking how staggered elections work in a couple of the scenarios. One could go further down a rabbit of extending senate terms and splitting the seats into four classes instead of three, or trying to model something resembling intrastate senate districts, but we’re not going to do that here.

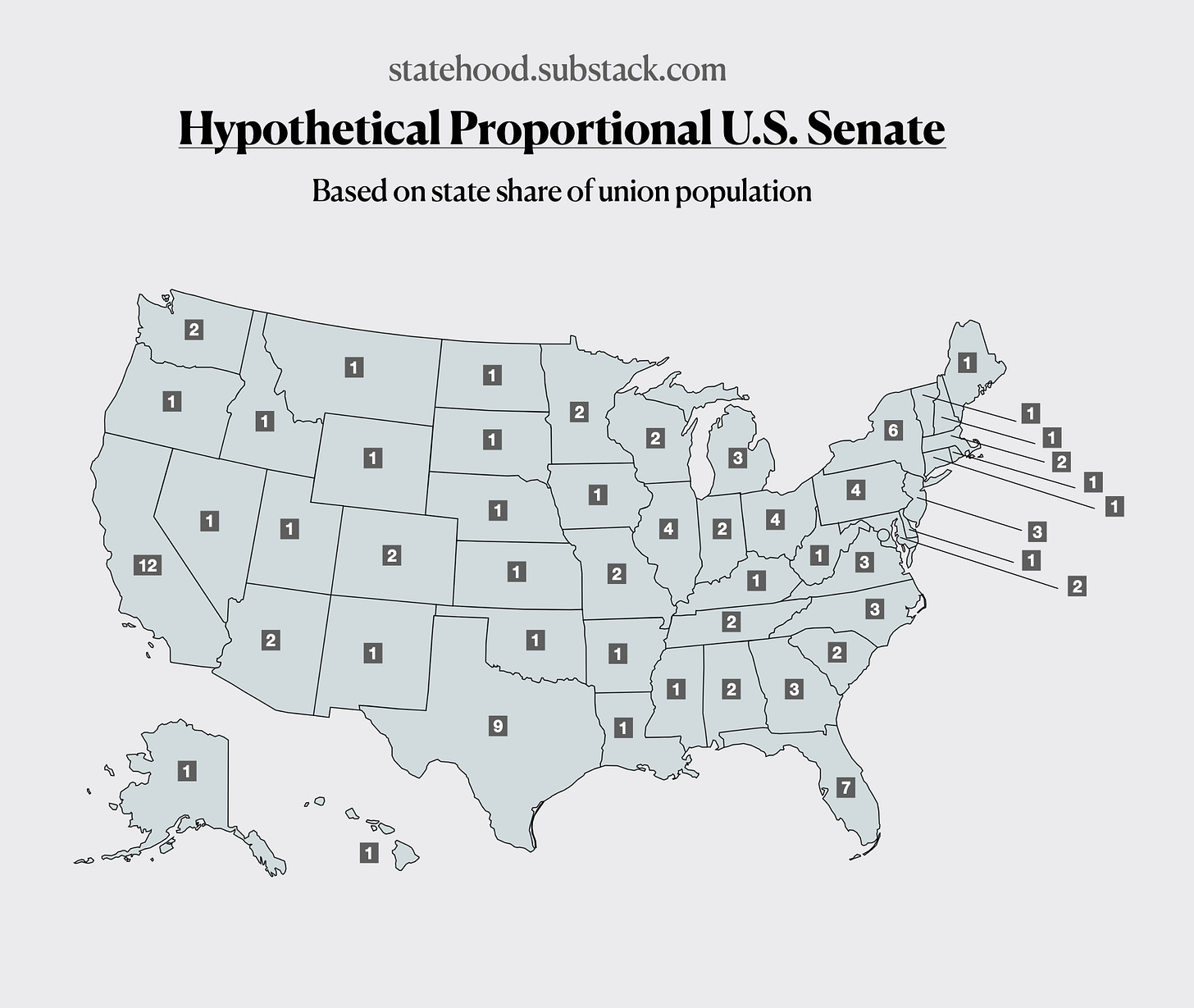

In our hypothetical proportional Senate, states are apportioned the number of senators reflective of their state’s percentage share of the union’s population. The smallest states that comprise less than one percent of the union’s population are awarded one senator. Of the 38 seats in these smaller states, Democrats hold 17 seats and Republicans hold 21. From there seats are apportioned by rounding to the nearest whole number. What we get is a new Senate with 111 senators and 56 votes needed to gain a majority.

Then we look at the average net Democrat margin across the last 100 regular full-term Senate races to determine the partisan lean of the states to inform how states are designated (mostly applying to Scenario A and C). Others use presidential data as a baseline thinking it’s an interchangeable proxy for Senate races. This is wrong because it fails to capture crucial and potentially decisive differences in margins including in decisive states. Here, we use Senate results to measure Senate performance.

We’re going to run through three scenarios of our hypothetical Senate.

Scenario A: Seats awarded to each party based on the party’s share of the statewide vote. In this scenario, we take the 2020 Senate elections as a base and instead of staggering elections by seat we stagger them by state. So states that held Senate elections in 2020 would have all of their seats up for election and seats would be awarded to each party based on the vote share.

(Side note: This scenario puts over half of the Senate up for re-election which itself would violate the rule of one-third of the chamber being up at a time but for the purposes of this exercise we’re going with it.)

In Scenario A, assuming all seats that aren’t up for election were allocated proportionally, Democrats would have won 27 seats in 2020 and a bare majority of Senate seats overall, 56 to Republicans’ 55 seats.

There is a caveat regarding California. California didn’t hold elections in 2020, but this scenario still supposes California’s 12 Senate seats were allocated 9-3, nine for Democrats and three for Republicans. California administers a blanket primary to determine its general election Senate candidates. For the last two elections both general election candidates have been Democrats. The ~70-30 allocation of seats reflects the total number of votes won by the ultimately victorious Democratic candidate and all votes cast for a GOP candidate in the primary. But under a Democrat vs. Republican general election, Democrats’ share of California seats would probably shrink by one or two seats. In Scenario A, that would cost Democrats the majority.

Scenario A is also reflective of the net gains each party would make by moving to a proportional Senate. Across all states, Senate Democrats would net 13 seats by gaining representation in eight states currently represented by two Republicans. On the other hand, Republicans would net 48 seats by gaining representation in 13 states currently represented by two Democrats. In the six states where representation is currently split, Democrats would total out at six seats and Republicans at seven seats.

This scenario also raises the question how expectations of Senate elections would change among electoral observers. In most states margins don’t change substantially and so allocations wouldn’t change in many states with two senators. But in states with three, four or more — if those states are competitive — like Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, Florida, Michigan, Virginia and Illinois, small gains by either party could make the difference in winning a majority of seats in each state. Winning two-thirds of the vote in Illinois, for example, would be enough to award Democrats three seats rather than two. In a state like Michigan, Republicans winning a majority of the vote there in Scenario A would award two of the state’s three seats to the GOP. Close contests in these multi-senator races might also increase the influence of states with one senator.

Scenario B: Winner-take-all situation. In this scenario, as with Scenario A, states rather than seats are staggered and whichever party wins more votes takes all of the senate seats in a given state. The state designations here are based on the winner of the last full-term Senate election in each state. 77 seats would be up for grabs with 44 of those seats leaning Democratic and 33 seats leaning Republican. In this case Democrats would expand their majority to six seats and would be competitive in North Carolina, Ohio and Florida of which if Democrats were able to sweep would give them a 20-seat Senate majority in this scenario. On the other hand, Republicans taking Nevada, Georgia and Wisconsin would give Republicans a two-seat majority.

In Scenario C, a portion of the seats in states with Class 3 elections are up. Shading is based on the margin by which voters elected members of each party over the last two full-term Senate elections in each state and yellow states denote states that are the most competitive. Here, we have a tie with each party needing four seats to claim a majority — of which could be attained in an election between parties or those between candidates, the latter of which would introduce more competition to each race.

If we interpret Scenario C with the real 2022 forecasts — whether or not we assume voters are electing parties or senators in these states — the proportional system would give Democrats effectively an extra seat. If we assume Democrats hold seats in Arizona, Georgia and Nevada and pick up seats in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, that’d give the party 53 percent of the chamber’s seats compared to the 52 percent they’d earn under the same result in the current system.

We could also imagine a blue wave: Democrats sweep all seven swing seats and notch two seats each in Ohio, North Carolina and Florida giving the party a 9-seat majority. On the other hand, a Republican wave: sweeping all of the swing seats and notching a seat in Illinois, New Hampshire, Colorado (and maybe even a seat in California!) giving the party a 6-seat majority. But in any case, we wind up about where we are in the current Senate.

One could add or subtract seats from each party’s column and come up with a number of other scenarios interpreted with a number of assumptions, but each of these indicate that the extent to which the current Senate composition radically departs from what it’d otherwise be in a more proportional system is overstated — in part because of the net change in seats between lower and higher population states in each party’s column.

It’s also worth mentioning that even in a radically proportional Senate where the states comprising less than 0.5 percent of the population are granted a half-vote, the chamber still winds up being roughly even with a Democratic advantage of 1-seat at best.

In a proportional system, it may be marginally more difficult for Republicans to earn even a bare majority of seats but not much more than it is now; the GOP unlike the Democrats would still struggle to crack 56 percent of seats — something they haven’t done in a century. On the other hand, Democrats could gain the most from arguably the least democratic option among these scenarios: winner-take-all.

In a futile attempt to entrench their own power, Democrats could admit the District of Colombia and Puerto Rico into the union of states but each of these new states would only be allocated one senator at most. In essence, the minority voters that would certainly gain a boost in representation in a Senate of equal suffrage would have their votes comparatively diluted in a proportional chamber — not to mention millions of black and indigenous voters in a number of lower population states.

All of this isn’t only predicated on a wild hypothetical but it also operates on an assumption that the coalitions and underlying assumptions of our politics would remain as is even after such dramatic reforms were enacted, again, by the vast majority of Americans it would take to ratify. By the time this were ratified and the inevitable compromises were made, California may be a conservative-leaning state while the next Silicon Valley crops up along the Mississippi Delta. Time and again we find the assumptions about the trajectory of our politics being disrupted and it’d stand to reason such a change to the union’s system of governance would result in the same. Once the hypothetical, lab-concocted new system devised by political scientists is exposed to oxygen, it could mutate or even light a fuse. Proportionality could increase the salience of state-centric identities and create new intrastate coalitions designed around protecting from legislative encroachments devised by more populous states. Reform may also require small and midsize states be compensated in the form of other constitutional protections as a result of their power being diluted in the Senate. And since constituencies to some extent transcend state borders, constituencies disproportionately concentrated in smaller states could wind up tipping the scales in closely contested larger states.

In any case, some of the most ardent critics of the Senate don’t find its structure nearly as objectionable as the perceived power it possesses in Congress, especially relative to the House which is why some of them have moved on from reforming or abolishing the chamber to simply neutering it of its power — another reform that’s going nowhere. Ultimately, objections to the Senate are less in favor of more or less democracy, or more or less representation, or more or less fairness, but any structure perceived to be impediments to a specific set of ends, regardless of how pyrrhic eliminating those impediments might be in the medium or long-term. Critics and defenders alike of American democratic institutions believe their own side has a larger mandate than it does and that the institutions need to be reformed to reflect that perception. This is ultimately the danger of toying with institutions; it isn’t that they cannot or should not be reformed but the extent the reforms are grounded in little more than expectations that turn out to be delusional is what begets the kind of goal post-shifting that turns democracies into autocracies.

Note: The original graphic depicting the number of seats apportioned to each state has been corrected for Massachusetts. The original graphic apportioned three senators; the correct apportionment for Massachusetts is two senators. The overall data was not affected. The Scenario A graphic has been updated since first being published to reflect the correct number of seats allocated to each party in Illinois: two senators per party, not one per party. The overall data was not affected.