Zohran Mamdani and the Suspension of Disbelief

The New York mayoral hopeful is a brand and great brands win fierce loyalty even if the product doesn't live up to the hype.

Let’s take a moment to break through the fourth wall of the commentary surrounding the mayoral campaign in New York City.

At this stage of the New York City mayoral race—an unrepresentative outlier among dozens unfolding across urban America—Democratic nominee Zohran Mamdani could probably reverse his positions, or even shoot someone on Bushwick Avenue, and still hold his lead and its a testament to his capacity to sell himself — and sell out as necessary.

Mamdani has successfully developed a personal brand that pegs himself as a policy-substantive candidate. On the brand side, a key to selling oneself as a politician is being able to engage your audience in a suspension of disbelief much the way great brands do regardless of their fidelity to the product. Audiences generally remain fiercely loyal to brands that make them feel a particular way or align with a certain aesthetic or set of values, sometimes, in the case of Mamdani, regardless of whether one rides the bus, lives in a rent-stabilized apartment, or owns a home in a safe neighborhood.

The second part is operating on the pretense of being a policy-substantive candidates even when the candidate has a distinct reputation for pitching policies that are empirically challenged or politically unworkable. In 2016, the current president had ideas about immigration and trade that he spoke about with urgency but nobody called him a policy-substantive candidate the way Mamdani’s defenders have which goes to show how low the bar is in an age dominated by cults of personality in terms of what constitutes substance.

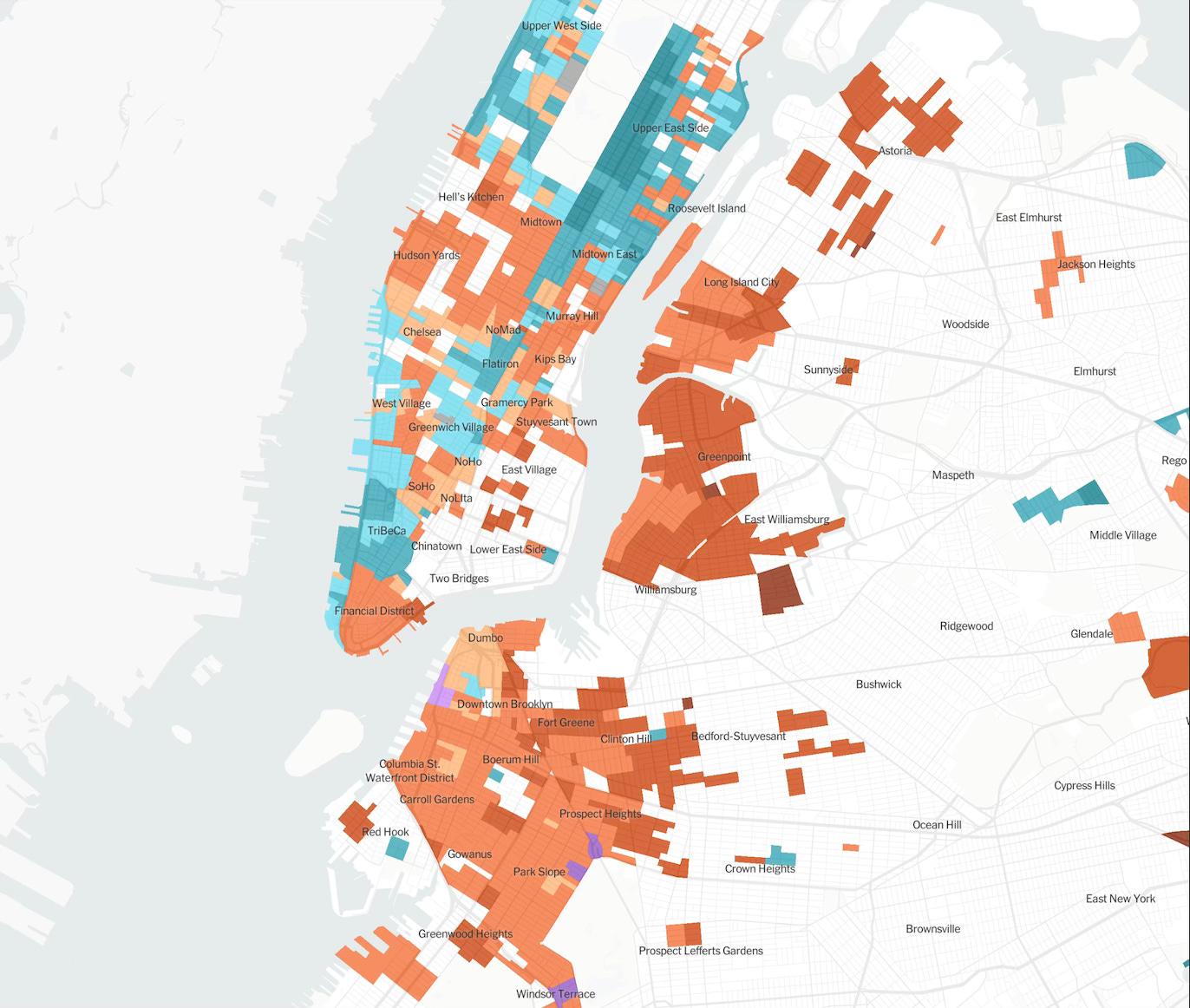

Though Mamdani has considerable support among middle-class New Yorkers, it was a surge among residents in heavily gentrifying neighborhood including what has been dubbed the “Commie Corridor”—the high-income riverfront Brooklyn neighborhoods packed with young professional progressives — that boosted him in the Democratic primary.

For these voters, Mamdani has tapped into the micro-brand culture trends that permeate social media. The heavy dependency on aesthetics for things like candles, sunscreen, apparel and energy drinks, but also the ubiquity of personal brand development on social media within the last decade reward campaigns with striking visuals and engaging personalities. This combined with his campaign have had something like a multiplier effect. A New York City voter, might have ambivalent feelings about political values but they might be more inclined to “wear the brand” if they see others they like wearing the brand. This reveals an irony of Mamdani’s appeal: among the smaller number of richer, politically-engaged, young professional supporters less likely to be impacted by his policies, his support was much stronger in the primary. Among the working class, who tend to be more politically detached, his support was weaker despite his supposedly policy-substantive platform being targeted at them.

As far as policy goes Mamdani’s platform mixes lofty ideals with the kind of grounded, fix-it-local pragmatism New Yorkers tend to appreciate. The most realistic parts—expanding childcare and making more bus routes fare-free already have been implemented to varying degrees. Expanded pre-K proved the city can scale early education, and the city has experimented with free bus pilots. Shifting some police duties to civilian responders or cracking down harder on negligent landlords could also move ahead without rewriting state law, just tightening what’s already there.

The most ambitious parts of his agenda—freezing rents, building 200,000 affordable units, launching city-owned grocery stores, setting a $30 minimum wage, and hiking taxes on the rich to pay for his agenda—are another story. Those depend on Albany’s permission, new funding, or both. Most will probably be shaved down into pilot programs, drawn-out studies, or smaller wins dressed up as big ones.

Among his most diehard supporters, though, Mamdani can do almost no wrong. They recognize to the extent he has to entertain feedback from Wall Street isn’t a sign of selling out but a prudent step to winning power — paradoxically the kind of pragmatism progressive populists would deride if his chief opponent, former governor Andrew Cuomo, were instead leading by 15 points. To this extent, there is no clear limit as to how much of his agenda Mamdani could voluntarily moderate before he’d cost himself meaningful support. Should he be elected, when the rubber meets the road, his mayoralty will likely resemble what New Yorkers would’ve gotten under someone like Andrew Cuomo, a former governor who has arguably the most progressive record of accomplishment of any elected executive in modern United States history.

Among the likelier outcomes of a Mamdani mayoralty will be that incrementalism—the very thing so often lambasted by people who call themselves democratic socialists. The rhetoric may be revolutionary, but the machinery of government isn’t—not simply because of corruption, bureaucracy, or special interests, but because of the accountability mechanisms and division of power that guarantee representation regardless of who’s in charge.

Acknowledging the limits of his agenda is the kind of buzzkill that doesn’t go viral among supporters. Conversely, his critics meanwhile are playing into the “kayfabe” nature of the race. The “communist” label they slap on him ignores the grind of budgets, state law, and administrative bottlenecks in seeing his glorious vision to completion.

But it’d be wrong to say that anyone — including many of Mamdani’s supporters, detractors, and those covering his campaign — care only or even primarily about the race’s implications for New York City. Remember, much of the political-media infrastructure is either located in New York, and those that aren’t are heavily influenced by commentators and tastemakers in the city. What looms over this mayoral race is the extent to which Mamdani’s victory or defeat will bolster high-profile figures like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez for higher office but more so pivot the national Democratic Party in a progressive populist direction.

All of this is despite the fact that the New York City electorate is less representative of the median New Yorker let alone the American voter. Virginia, which also has a gubernatorial election this year and is at least within the ballpark of the median American voter, will likely elect its first woman governor with decent odds of it being among the widest margins for a Democratic gubernatorial candidate in decades — and yet few reporters are probing national Republicans over their views on Abigail Spanberger, and nobody really is framing the Virginia race as defining the direction or tone of the national Democratic Party.

Much has been commentated on about the parallels to the popularity of Mamdani and Trump — that they are populists talking about “real” stuff, like border security, trade and high prices. And there is a degree of truth to that despite the aggrandizement of a public executive’s influence over prices. But what’s primarily propelling these candidates isn’t what we think of as substance or, believe it or not, necessarily rational.

Among comedian Jerry Seinfeld’s greatest work wasn’t a stand-up routine but an acceptance speech for an advertising award he was given, in which he roasted the entire pretense of the affair:

I love advertising because I love lying. In advertising, everything is the way you wish it was. I don’t care that it won’t be like that when I actually get the product being advertised because in between seeing the commercial and owning the thing I’m happy and that’s all I want.

Despite how much trash is leveled at the current president, the former New York governor, or current city mayor for that matter, the more compelling brand will probably win out because when it comes to any sort of campaign, it’s less about what you what people to think than what you want them to feel. The best brands don’t need to deliver, they just need to look like they can to enough people.

“Just a week after the October 7th attacks, while rockets still rained down on Israeli civilians, Mamdani accused Israel of genocide — a slander he continues to repeat. He will not condemn the phrase “globalize the intifada,” and he’s proudly appeared with antisemites like Hassan Piker, who once said: “America deserved 9/11.”

This kind of rhetoric fuels the hatred that has led to violent demonstrations and deadly attacks. It is unthinkable that the city with the world’s largest Jewish population could elect someone who refuses to understand this.” Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz’s full commentary on Jewdicious: https://tinyurl.com/5589hrh5