Grover Cleveland's Comeback

Within four years after the ex-president returned to office his party lost Congress, the presidency and the states for a generation.

I don’t know about you, but when I was in grade school, the Gilded Age was a pretty neglected period in United States history class—teachers seemed to largely hop over the period between the end of Reconstruction and the Progressive Era. In the current period, though, the parallels to the Gilded Age are pretty stark. Does it supply clues as to what’s to come this year and in the years to come?

After the Civil War, the U.S. reunited and rapidly industrialized. Wartime production, new banking and corporate forms, and a flood of railroad building emerged. National policy often favored growth through tariffs, land grants, and loose regulation. Wealth concentrated, city cores urbanized, labor unrest grew, and politics became more tangled in corporate power than it had been. Not to mention the partisan media and the heightened salience of immigration and civil rights issues.

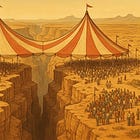

It was also a window of time within which the Union saw some of its most contested presidential elections in history, as well as the last time (and only other time) a president won a re-election bid to a nonconsecutive term. That, in turn, was followed by the opposition controlling the federal government for a generation.

Grover Cleveland and Donald Trump share the rarest American political rhythm. Both were treated as mistakes the system would correct, and both came back anyway. And in both cases, the comeback was not powered by a makeover but by an old fixation that grew louder while they were gone. For Cleveland, the fixation was tariffs. Protection was a disguised transfer from ordinary consumers to organized producers, the argument went. When people started to feel that after four years of Benjamin Harrison, Cleveland gradually became more validated and started sounding like the only major figure who had been insisting the country was paying a hidden tax to the well-connected. Though a fan of tariffs, what catapulted Trump back into the White House, in part, was border security—but also the stark contrast to his predecessor (and successor). Until Governor Greg Abbott of Texas began bussing migrants north from a U.S.-Mexico border that saw a surge in encounters, the migration issue never left the minds of the American public. Biden ran on normalcy, and between disastrous fiscal policy, chaos at the border, and a botched withdrawal from Afghanistan, Trump benefitted from a sense of buyer’s remorse that Kamala Harris couldn’t overcome.

The years between the 1880s and the 1910s are useful here because the parties were not ideological monoliths. They struggled much the way the current parties have, between factions. They argued internally over whether to lean into populist anger or to reassure business and institutions.

Democrats start the period with Cleveland’s posture, which is better described as reformist restraint than as modern liberalism. It was anti-machine, suspicious of patronage, skeptical of expansive national programs, and oriented toward credibility in finance and administration. After the crash in 1893 and the mid-1890s trauma that followed, Democrats did not glide smoothly toward the center.

William Jennings Bryan came along as something of an insurgent and turned Democrats into a vehicle for moralized economic populism, aimed at concentrated power and the financial establishment, and it gave the party a mass style of politics that was louder than Cleveland’s own. But Bryan failed to overcome McKinley in two consecutive presidential elections. Bryan would also lose a third bid as the Democratic nominee in 1908 against William Howard Taft. Democrats pivoted to Alton Parker, a more conservative establishment Democrat, but he wasn’t able to unseat Roosevelt, who, while popular at the time, had begun seeing splinters within his party that McKinley had been able to keep together before his assassination. Eventually, Democrats landed on a different synthesis under Woodrow Wilson, a sweet spot of sorts between progressivism and managerialism, notwithstanding Wilson’s tarnished legacy as a segregationist.

As for Republicans, they had been the reform party from the post-Civil War era through Reconstruction and into the stratified Gilded Age. By the 1900s and 1910s, the Republican argument became increasingly nationalistic. Roosevelt believed it to be the duty of the federal government to curb abuses within the system and called for a unity that wound up involving a considerable amount of consolidation and anti-institutionalism. His successor, William Howard Taft, embodied a progressive conservatism that combined the antitrust and reform-mindedness of the Roosevelt period with a regard for institutions. In 1912, after 16 years running the federal government, Roosevelt, the third-party Progressive nominee, challenged Taft, the incumbent Republican president, splitting the vote and handing a landslide victory to Woodrow Wilson.

The Republican triumph that begins in 1894 is usually attributed to one thing. The country fell into deep economic distress after 1893, and Democrats were the party in power. Republicans were able to tactfully do what Democrats are trying to do today, which is bridge the divide between the progressive populist wing and the market-oriented technocratic wing—and you can see this in the breadth of popular news opinion, which leans left, in Democratic primaries across the country, and among the prospective presidential candidates.

For a time into the turn of the 20th century, Republicans looked like the party with a theory of modernity. In an era when the federal government was becoming a more consequential actor, the party that seemed more at ease with centralized power kept finding ways to win even when it was internally divided. More broadly, Roosevelt’s strongman “New Nationalism” style politics treated fragmentation as a problem to be solved and treated national authority as the instrument for solving it. The reform impulse became less about leaving space for local variation and more about building a coherent national state that could manage the economy and discipline power. It’s also the case that state and regional polarization, and the limited though material success of third-party candidates, often foiled either party from earning popular majorities into the 1900s.

That brings the story back to 2026. The safest prediction in American politics is that the president’s party usually bleeds seats in midterms. The conventional wisdom is that Republicans lose the House and possibly the Senate this year.

The harder question is scale. A true 1894-style catastrophe is less likely now because polarization and national sorting act as guardrails. And it appears, for now, although things can change, that Democrats aren’t leading by a larger margin than they were compared to the 2018 midterms—but it’s also the case that polls in Virginia and New Jersey last year underestimated the turnout gap between Democratic- and Republican-leaning voters. There are also fewer competitive districts—but it’s also the case that, eventually, after years of tight margins, things break decisively for one party within a broader realignment.

The 1894 number is worth keeping in mind as an image even if the modern translation is smaller. Republicans gained on the order of a hundred-plus House seats in that midterm and while it’s hard to see such a swing this time around, it’s a reminder that a governing party can go from restored to repudiated quickly when the public concludes that the return solved one problem and either created or exacerbated others.

Cleveland’s tariff focus helped bring him back, but it did not immunize his second term from conditions, factional splits, and the optics of federal power. If 2026 becomes a referendum on whether the country feels more stable and less strained, Republicans have a path to limit losses—particularly if rifts between Republican congressional candidates and Trump on foreign intervention and tariffs become more pronounced and less risky. Conversely, if the midterm becomes an indirect repudiation of the president, there becomes a certain inevitability of losses — something of a correction to the correction that we’ve seen time and again.