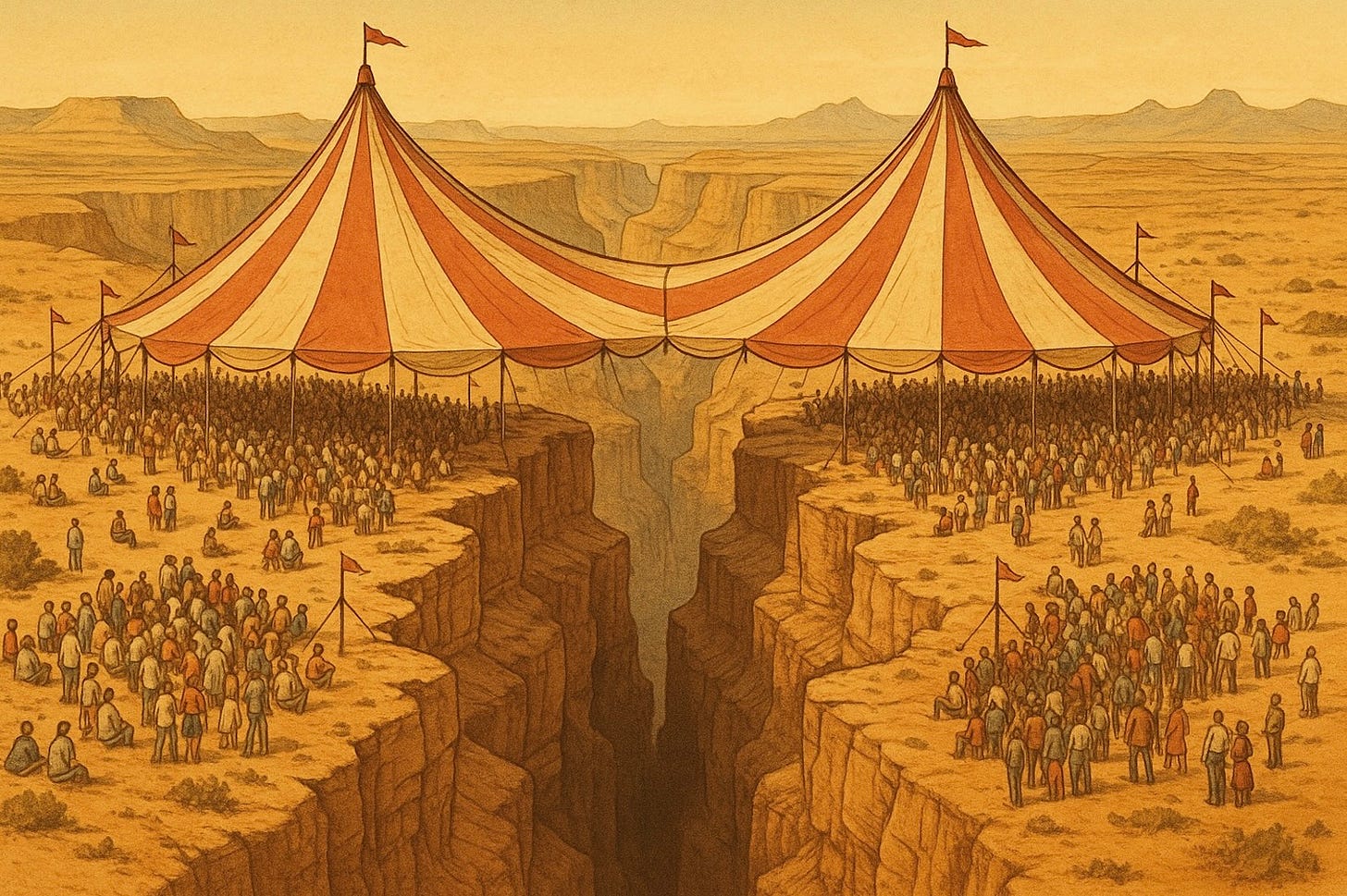

Can Democrats Expand Their Tent on Economic Rage?

Affordability is a winning message but the left risks a fumble if they allow it to become a euphemism for economic revolution

Since Democrats’ defeat in federal elections last year, a consensus has all but emerged that a major part of their corrective strategy is to muzzle their cultural progressivism and aim to build a broader coalition that can earn the party durable multi-majorities again. A core rift in the party is whether to move a leftward populism or toward the center on economics, but also the tenor of economic messaging.

In a recent New York Times op-ed, veteran Democratic strategist James Carville called for Democrats to pursue an “aggressive” and “sweeping” agenda of “pure economic rage.” After months of rising groceries and more public opinion data, Democrats and their broader brain trust think they’ve found a focus around which to bridge the intraparty rift, and that focus is “affordability” — a neutral and salient word recognizable by the layperson and that breaks from both Bidenism and “socialism”. It’s legitimately the best idea Democrats have going into the next three years. But “affordability” may prove to be treacherous if the term becomes a euphemism for left-wing economic populism from the Biden era and doesn’t resolve or at least recognize the differences that do exist on vibes (which do matter) and political strategy in the aftermath of the shutdown.

To Carville’s credit, he was quite a vocal critic of the left’s fixation on identitarianism and cultural condescension before it was widely acceptable in entrenched Democratic circles to push back against it. But the now banal observation that Democrats went overboard on culture really obscures the party’s extremism on economics and fiscal policy during the Biden presidency, which was marked by the kind of sweeping policy Carville seems to imply Democrats need to embrace.

But before getting into Democrats and affordability, it’s worth breaking the fourth wall to acknowledge how much of the politics surrounding the economy among journalists, the president, lawmakers and experts is a performance in the suspension of disbelief.

The politics of economics is mostly signaling control over the economy, including prices, that presidents do not have. Presidents with Congress can certainly raise prices but even prior to Trump’s tariffs, there was little Trump and Republicans could do to lower the price of consumer goods, the way there was little Biden and Democrats could do to lower inflation other than not pouring money into the economy. Most policies that could be traced back to a president or Congress take years, and even then it’s difficult to attribute macroeconomic outcomes to the president’s policy. A poll from last year found Americans divided on perceptions of presidential influence over consumer prices, with 25% saying the president has a lot of or total control, 35% saying “some control,” and 33% saying either not much or no control. The president ran and won on reducing prices that he doesn’t have the power to reduce — and yet, this false claim of authority is one that presidents never get fact-checked on by reporters in part because a false attribution of power drives storytelling. Out of one side of their mouth reporters clutch pearls over autocracy and out the other attribute job creation, consumer prices, GDP growth and unemployment solely to the president. If the political strategy around affordability feels amorphous — whether to lead with pragmatism or rage, moderation or zeal — it’s because it’s premised on a figment that makes debates over affordability feel like fighting with a cloud. But we’ll accept the premise and instead treat economics as a proxy for how best to win at politics at the risk of perpetuating a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The first pitfall Democrats may face is allowing “affordability” to become a euphemism to bait suburbanites with moderate rhetoric into a more progressive agenda. Affordability concerns center around food and housing — the latter of which is much more localized. The rift in the party is whether to interpret concerns over momentary food and housing costs as demand for restructuring the economy, or alternatively, to advance minimally disruptive policies perceived ease upward pressure on prices. In either case, it’d be wise for either faction to say what they mean and do as they say.

This contrasts the run-as-a-moderate-and-govern-as-a-progressive strategy which was the cornerstone flaw of the Biden presidency, indistinguishable on economics from what one might imagine a Sanders presidency could have pursued given razor-thin congressional margins. Joe Biden campaigned on moderation and a return to normalcy but was pulled leftward on economics in a fit of, if not economic populist rage, then economic populist fervor having been flattered that he could cement his legacy as a modern-day Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, passed in early 2021 roughly three months after a $900 billion bill poured a massive amount of demand into an economy well on its way to recovery. Combined with very generous unemployment benefits and a new entitlement program, the child tax credit, it overshot and hiked inflation to the highest level and for a longer period of time than any other developed nation that experienced inflation spikes despite the expertise of Nobel laureates advising the president that the inflation that wouldn’t be an issue (but was) would be transitory (which it was not).

Nor was it only progressive populists but center-left technocrats who were vouching for fiscal maximalism out of a belief that Democrats’ Great Recession response wasn’t strong enough but also out of spite for the GOP’s fiscal hypocrisy under Paul Ryan’s speakership. These factions, along with an outcomes-driven congressional press corps badgering senators to abolish the filibuster, also pushed to pass several trillions more in new spending, including the failed Build Back Better colossus, as inflation was rising to 7% before it’d max out at 9% nearly a year later. There were comparatively defensible pieces of legislation like the bipartisan infrastructure law and the CHIPS and Science Act, but also the Inflation Reduction Act involving industrial policy, climate subsidies, and place-based spending with weak fiscal guardrails, all framed as “middle-out” economics. The administration extended the federal eviction moratorium even after legal warnings, kept student loan payments paused for years, attempted a sweeping one-time cancellation that the Supreme Court rejected, and then pursued backdoor relief through new repayment rules. These executive maneuvers certainly did not begin with Biden, but they escalated under him, given the crippling pressure he was under from his left, and re-established a precedent of executive overreach currently being exercised by Trump. Finally, on trade, Biden normalized Trump-era populism rather than reversing it: he kept most tariffs in place, added new ones, and leaned into “worker-centric” trade and Buy American rules that privilege protected sectors and union jobs over the kinds of consumer prices that have risen since. So the U.S. already had one economic populist moment with Joe Biden and Democrats from 2021-23.

The ways Democrats can sidestep this problem are by, first, recognizing that there are multiple ways for Democrats — at the local, state and federal level — to win on affordability, but that will involve party leaders recognizing that a broad range of candidates on vibes, rhetoric and policy will need to be tolerated, if not encouraged. Among the very online, there’s a debate over whether moderates or progressives have a better electoral track record, and much of that boils down to methodology and classification choices.

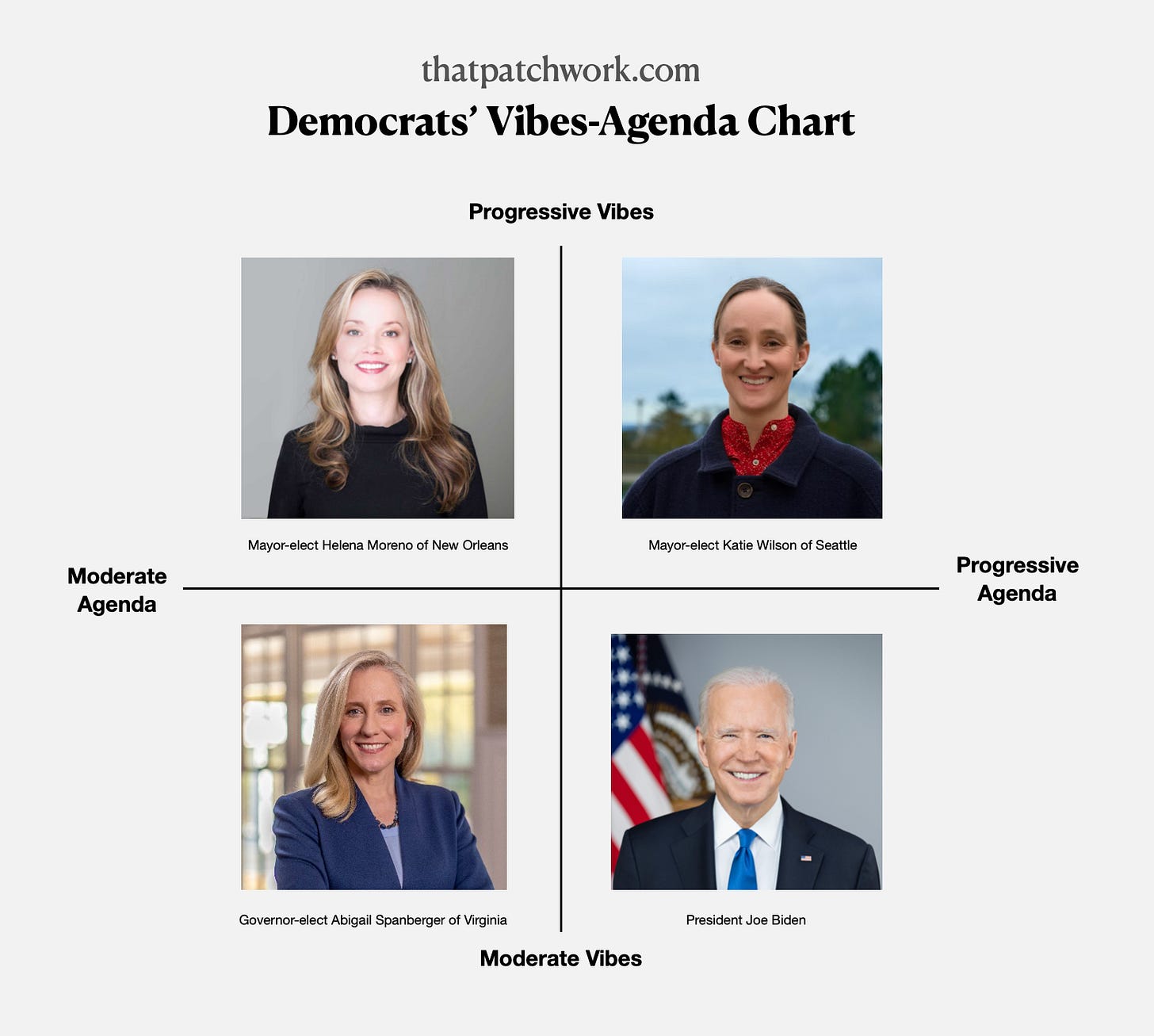

In simpler terms, one can imagine a four-quadrant typology: moderate vibes–moderate agenda, progressive vibes–progressive agenda, progressive vibes–moderate agenda, moderate vibes–progressive agenda. There are examples of three of these being rewarded by voters.

Governor-elect Abigail Spanberger of Virginia would be a prime example of moderation on both vibes and agenda, winning by the widest margin for a Democrat since segregation. For progressive on both counts, Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani of New York or Mayor-elect Katie Wilson of Seattle would be examples of candidates who earned half the vote on leftward platforms.

Then, there are your progressives in the streets and your moderates in the sheets — these are most of the mayors who were elected or re-elected in major cities this year, including mayors-elect Helena Moreno of New Orleans, Corey O’Connor of Pittsburgh, Mary Sheffield of Detroit, and Cara Spencer of St. Louis — all prevailing over candidates to their left in primary or general election races. While affordability was emphasized to varying degrees in these campaigns, public safety, budgeting, economic development and anti-corruption were all major issues. These candidates succeeded in making order and responsible governance sound progressive throughout their messaging.

Finally, there are the moderate-on-vibes and progressive-on-agenda crew, the quintessential recent example being Joe Biden. Progressivism is proudly disruptive, and delivering disruption on an expectation of stability risks disastrous electoral results. This contrasts Barack Obama, who did the inverse by governing modestly to the right of his campaign rhetoric and lives on as the most popular political figure among Democrats and one of the most popular among the American public. Crucially, none of these urban mayoral candidates ran on economic populist rage.

But if affordability is the issue that transcends Trump and can unite Democrats for years, then resistance to Trump is the issue that can unite them now — but even anti-Trumpism reveals a rift within the party that calls back to the same one revealed during Biden’s tenure: Democrats aiming to govern more disruptively than their unifying fight against Trump suggests. Figures like Chris Murphy of Connecticut and Chris Van Hollen of Maryland have criticized Democratic leadership for not fighting hard enough, building on the meme that weak Democrats are busy writing strongly worded letters while Trump dismantles the federal government. In fact, Democrats had notched legal successes against Trump’s agenda early in the year, unsexy as they may read, including blocking appointments and legislation via the filibuster.

But it isn’t clear what the progressives in Congress precisely have in mind by wanting Democrats to “fight” harder that doesn’t involve the Republican Party capitulating to progressive public policy. After all, this was the “fight harder” strategy during the shutdown: ground more flights and furlough more workers until the Republicans pass an extension of the Affordable Care Act tax credits. This proved to be untenable for at least eight Democratic senators (possibly more, but who faced greater electoral risk from sticking their necks out), including those like Tim Kaine of Virginia with a materially impacted constituency. Given that, the demand for Democrats to wait for Republicans to pass a key Democratic priority wasn’t practical. And as a matter of principle, nobody would expect the inverse — for progressive senators to include a Republican priority in a continuing resolution as a condition for re-opening the federal government. Mind you, all of this is occurring parallel to progressives and now a select number of populist Republicans who advocate for eliminating the filibuster, the primary means by which political minorities have checked the excesses of the governing majority.

The question of whether Democrats should moderate or radicalize is as much institutional as it is economic or cultural. Right now, federal politics exists in a world bereft of principle in large part because of the example set in the current White House. In turn, progressives and the president are operating from the same playbook: to use whatever means available to block power and to then dispose of those same means when power is acquired.

The next two years, let alone four or eight, are likely to be disruptive, and our capacity and understanding to tackle the largest problems have changed since the 2010s. On the S-tier progressive policy trifecta — inequality, climate change, and health care — new developments at home and abroad, along with influential new insights, are beginning to challenge the maximalist policies the left treated as no-brainers a decade ago. Europe’s brittle, risk-averse social democracy has underscored the importance of private investment and the difficulty with taxing wealth and figures like Bill Gates are reframing the fight against climate change away from apocolypticism. With China developing a military space program and the U.S. federal government nearing $40 trillion in debt, enough to make even center-left analysts anxious, the D.C. brain trust is likely to recalibrate around what is actually feasible.

But if Democrats decide that they want to move the party, and the union, left on economics — higher taxes on the wealthy, new and expanded entitlement programs, tougher anti-trust, the centralization of medical insurance, and a continuation of industrial policy — they should unapologetically run on that. They should listen to Carville, win if they can, and prepare to moderate. But whatever they do, they should steer clear of selling economic populism with a brand of mild-mannered disciplined pragmatism that they have no intention of living up to.