Most Americans Distrust The Feds And Say They Are Too Powerful

Meanwhile, political leaders and the media embolden central power by insisting more disputes be nationalized.

In closing out the year, I wanted to draw attention to an overlooked polled conducted by Gallup from earlier this year that sort of breaks the fourth wall of our hyper-nationalized discourse to acknowledge how at odds the public views are with a political media industry that can’t imagine any problem not being resolved by the federal government.

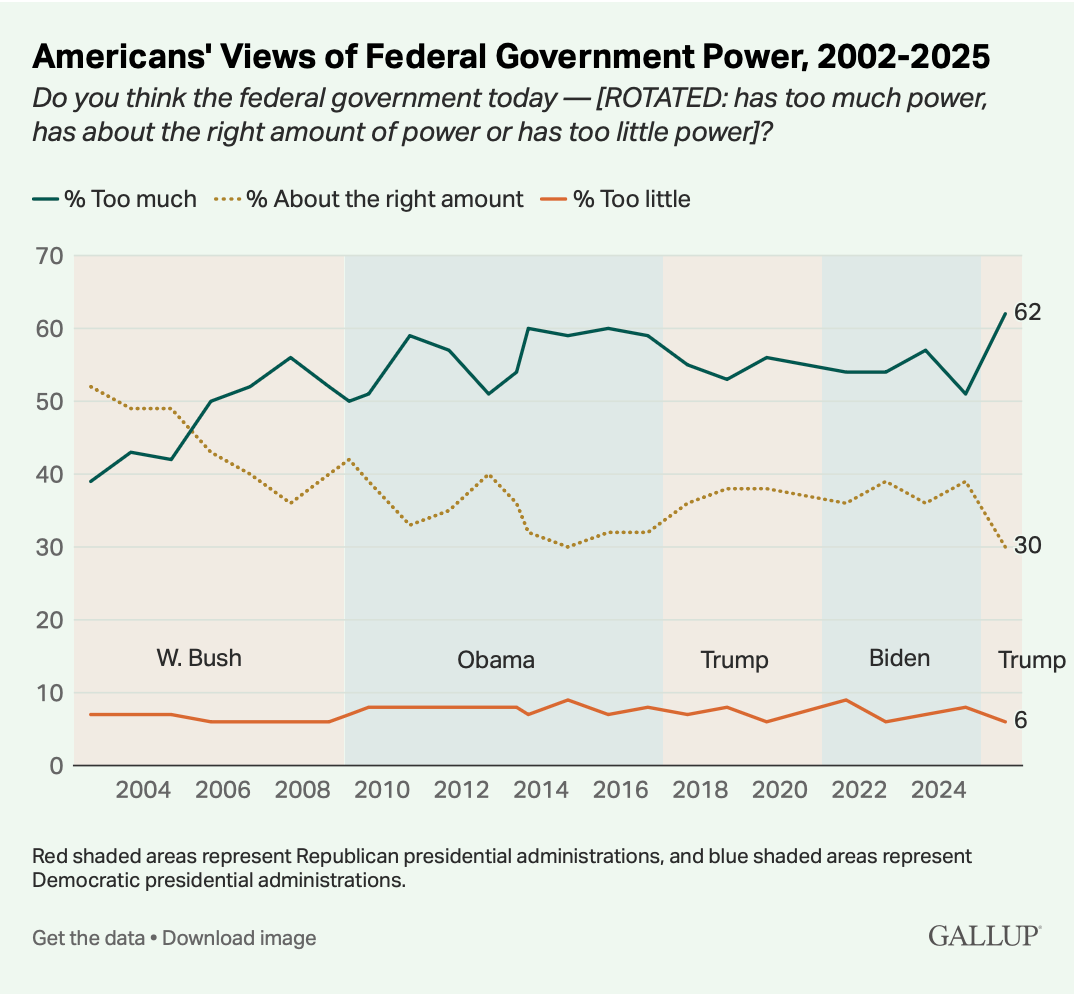

According to Gallup in its October poll, sixty-two percent of Americans now say the federal government has too much power—a record high in Gallup’s trend back to 2002. The topline is notable, but the coalition is the story: Democrats swung in a year from 25% saying “too much power” to 66%, making them more likely than Republicans to voice overreach concerns for the first time since the mid-2000s. Treat that as more than partisan weather. It suggests centralized power can feel threatening even to many voters who typically prefer national capacity. Meanwhile, 6% said the federal government has too little power.

That broad unease sits on top of a broader collapse in faith. In 2023, Pew found only 16% trust the federal government to do the right thing “just about always” or “most of the time,” and 59% say their main feeling toward it is frustration. Pew also shows how federalism anxiety cuts both ways: 41% are extremely or very concerned the federal government is doing too much on issues better left to states, while 41% are extremely or very concerned that states aren’t willing enough to work with the federal government.

The favorability numbers point in the same direction. In late 2023, Pew found 22% favorable toward the federal government versus 50% for state government and 61% for local government (all down from a few years earlier). That doesn’t prove Americans are decentralists. It supports a simpler critique: our political culture treats legitimacy as if it can only be manufactured at the top, even as many people experience government as least credible at the top.

This is where the media frame matters. National politics is covered as if it’s the only politics that counts. Governors become presidential tryouts. Mayors become culture-war avatars. State legislatures become props in national dramas. Policy differences get narrated as threats to “the country,” not choices within a federated democracy. That frameI trains audiences to expect the presidency and Congress to settle every conflict, and it rewards politicians who route more problems upward. But when state and local government are acknowledged, when they are included in polling, when polls disrupt the presupposition that the federal government is not too powerful, Americans express a discomfort and distrust of center power.

Now add the detail that makes the Gallup trendline harder to dismiss as mere out-party alarm. Yes, the 2025 spike is tied to the start of Trump’s second term, and Gallup points to expansive executive action as a likely driver. But even during the Biden presidency, one in four Democrats already said the federal government had too much power. That’s not some fringe reflex. It’s a reminder that skepticism of centralized authority isn’t confined to the right—and that the premise “national power is the obvious solution” was never as universally shared as elite discourse assumes.

One caveat, briefly: “too much power” doesn’t specify which branch, which policy domains, or what alternative people prefer. Public opinion can want stronger federal capacity in some areas and tighter limits in others; more national guarantees and more state variation. The point isn’t to pretend public opinion is coherent — and so long as it is not, it’s a stronger case for resolving public policy challenges at first locally and supporting local institutions in executing those policies.

So in the new year, I want to treat Gallup’s 62% less as a prompt for further exploration. I want to foreground what we rarely measure: where people think they can realistically be heard, what they think state and local institutions are for, and how often national politics is taking credit or blame for outcomes that are being produced locally. And I want to interrogate the media premise directly: how Washington-first storytelling raises the stakes, rewards maximalism, and puts pluralism on a destructively divisive path by insisting on a uniformity that will not be. Put another way, I want to aim to better understand what people believe democracy is for and what they believe are the institutions that maximize representation.

All of this is particularly important to probe given how the usually implicit and sometimes explicit premise on which much of the political discourse operates is that we should be striving for unifying conformity, smoothing over legal patchworks, and deferring to central power which has unparalleled expertise and wisdom. But as we’ve seen with the current administration and the preceding one, the union trained to concentrate power will keep rediscovering—under changing parties—how dangerous that concentration feels once the hand on the lever isn’t the one side may trust.

Perhaps there might be a link between the intrusion of an authoritarian "unified presidency" and distrust of the federal government. The abdication of Congress as the "voice of the people" to dictate to Trump and his federalization of the military to intervene in state affairs also contributes to "distrust" of the overreach of the Federal Government.