The Supreme Court's Next Act on Voting Rights

By centering geography, as most states already do with legislative maps, the Court could revitalize local representation in Congress.

This term, the U.S. Supreme Court took up a case in oral arguments — Louisiana v. Callais — that could reshape the electoral districts drawn by states that elect state and federal lawmakers. Observers posit that the Court is poised to gut Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, designed to ensure a certain number of majority-minority districts exist to retain the ability for racial minority voters to elect their preferred candidates. The plaintiffs argue that forcing states to meet racial targets is unconstitutional. A previous case sheds light on how I think the Court could — or could not — rule and the extent to which the federal electoral ramifications would be exceptional.

In Louisiana, the case centers on Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, a key part of the law that bans voting rules or district maps that make it harder for racial or language minorities to have an equal voice in elections. One way states have sought to do this is by creating majority-minority districts — the surest way minority voters can elect their preferred candidates.

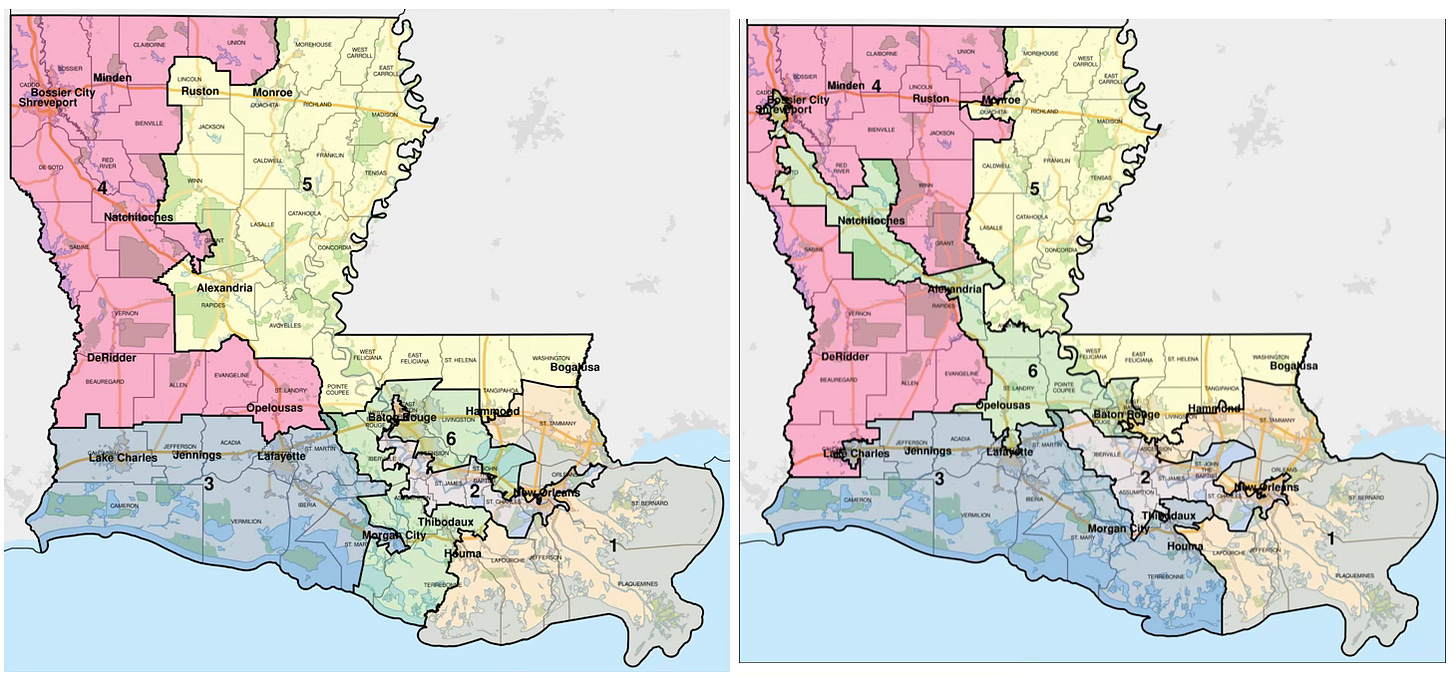

Louisiana created a second majority-black congressional district after its hand was forced during previous litigation that argued the state’s packing of black voters into a single district diluted black voters’ overall representation in a state where they constitute about a third of the population. Now, the state is arguing that the district it was forced to draw is a form of racial discrimination, even if the ends, defendants would argue, are designed to protect minority representation. For decades, Section 2 has been used to challenge unfair maps without proving intentional racism — only that the results are discriminatory. Now, the Court is being asked whether that very rule is constitutional, or whether requiring states to consider race when drawing fair districts violates the Constitution’s promise of equal protection.

I’m not a legal expert, but I do want to observe a path the Court could plausibly take based on another case also involving the Voting Rights Act — one that reignited litigation around the landmark law — Shelby County v. Holder.

In that case, the Court struck down Section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act, nullifying Section 5’s federal preclearance requirement for states with histories of racial discrimination. The coverage formula, based on outdated 1972 data, had never been revised despite congressional renewals. Chief Justice Roberts argued that “our country has changed,” and laws must reflect current conditions. Importantly, in a related preceding case out of Texas, Austin Utility District v. Holder, Roberts signaled to Congress that the data governing Section 5 was outdated. At the time the ruling came down, Democrats held a nine-seat majority in the Senate and a substantial majority in the House. Congress didn’t act, and so Section 5 remains not so much “gutted,” as critics often write, but neglected by a more polarized Congress.

As interesting in this case is the extent to which members of the Court may be amenable to a new standard that places local geography at the heart of fair representation. In Callais, the Supreme Court seems to entertain that idea, based on analysis from the oral arguments. During oral arguments, several justices signaled interest in narrowing Section 2 rather than dismantling it. Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kavanaugh questioned maps that link distant black communities, suggesting states should prioritize compact, locally coherent districts before considering race. Kavanaugh’s comments about a “time limit” on race-based remedies pointed to recalibration, not repeal, while Justices Alito and Gorsuch stressed that race cannot outweigh traditional map-drawing principles. Together, their questioning hints at a “local-first” standard — one that elevates geographic integrity and community boundaries, curbs Section 2’s scope, yet still allows minority influence to emerge naturally where population patterns support it.

In Louisiana specifically, a “local-first” ruling would have immediate and tangible effects. The state’s current map, which added a second majority-black congressional district under federal pressure, links distant communities from Baton Rouge to Shreveport with little geographic or cultural continuity. If the Court adopts a standard requiring compactness and local coherence before racial considerations, Louisiana could be permitted to revert to a map more reflective of its parish boundaries and regional identities. Such a change would likely reduce the number of majority-black districts but would emphasize political representation grounded in shared local interests.

One 2019 survey finds that 37 states require compact state legislative districts, while 21 states require compact congressional districts. Such a pivot, if the Court were to take one, would be well within a standard that a large majority of states apply in congressional or state legislative redistricting, or both. However, “even where compactness standards exist,” the study finds, “courts have difficulty enforcing them. There is no clear threshold at which a given compactness measure’s numeric value indicates a violation.” Iowa, Colorado, and Michigan, for example, have quantitative measures. Other states rely on phrasing like “reasonably compact.” It’s also worth mentioning that a “local-first” compactness isn’t intended to strike a proportional partisan balance by one measure or another. It is designed to represent communities with like interests based on geography. Everything else is secondary. After looking at some congressional and state legislative maps, it becomes easy to guess which states have compactness requirements and which don’t.

An even more interesting question is the opportunity such a ruling presents in indirectly tempering political gerrymandering as a second-order effect, which the Court declined to weigh in on back in 2019 in Rucho v. Common Cause.

State courts could cite the Callais opinion as persuasive authority under their own constitutions to strike down extreme partisan gerrymanders, while legislatures and redistricting commissions might codify those neutral principles into law. Such language could elevate the integrity of local geography as a predominant factor and could be incorporated into how states shape new maps.

Such a decision could make sprawling districts easier to attack, particularly for Democrats who would be eager to cite how certain state lawmakers’ approaches to redistricting may contrast with that of the conservative Supreme Court. Even if the ruling were to apply only to race-related cases, the logic could make its way further into popular discourse, onto referenda, and perhaps into state constitutions. Or not. Such a ruling would almost certainly secure broad discretion for states, perhaps to keep districts with high proportions of minorities local and compact while others remained sprawling.

Whatever the outcome, Callais will test whether the Court still trusts states to govern their own representation. A “local-first” standard wouldn’t end the politics of race or power, but it could quietly shift where those fights are fought. Even so, there remains work for Congress to take up in restoring voting rights protections before, in 2031, the Voting Rights Act is set for renewal.

Beyond That Patchwork

An assortment of recommended media

“Democrats and ‘The Vision Thing’” by Ruy Teixeira, The Liberal Patriot

“Stolen Louvre Jewelry Worth Over $100 Million, Paris Prosecutor Says” by Ségolène Le Stradic, The New York Times

“Record-High 62% Say U.S. Government Has Too Much Power” by Frank Newport, Gallup

“Deadbeat” by Tame Impala