Who Can Deny An Election?

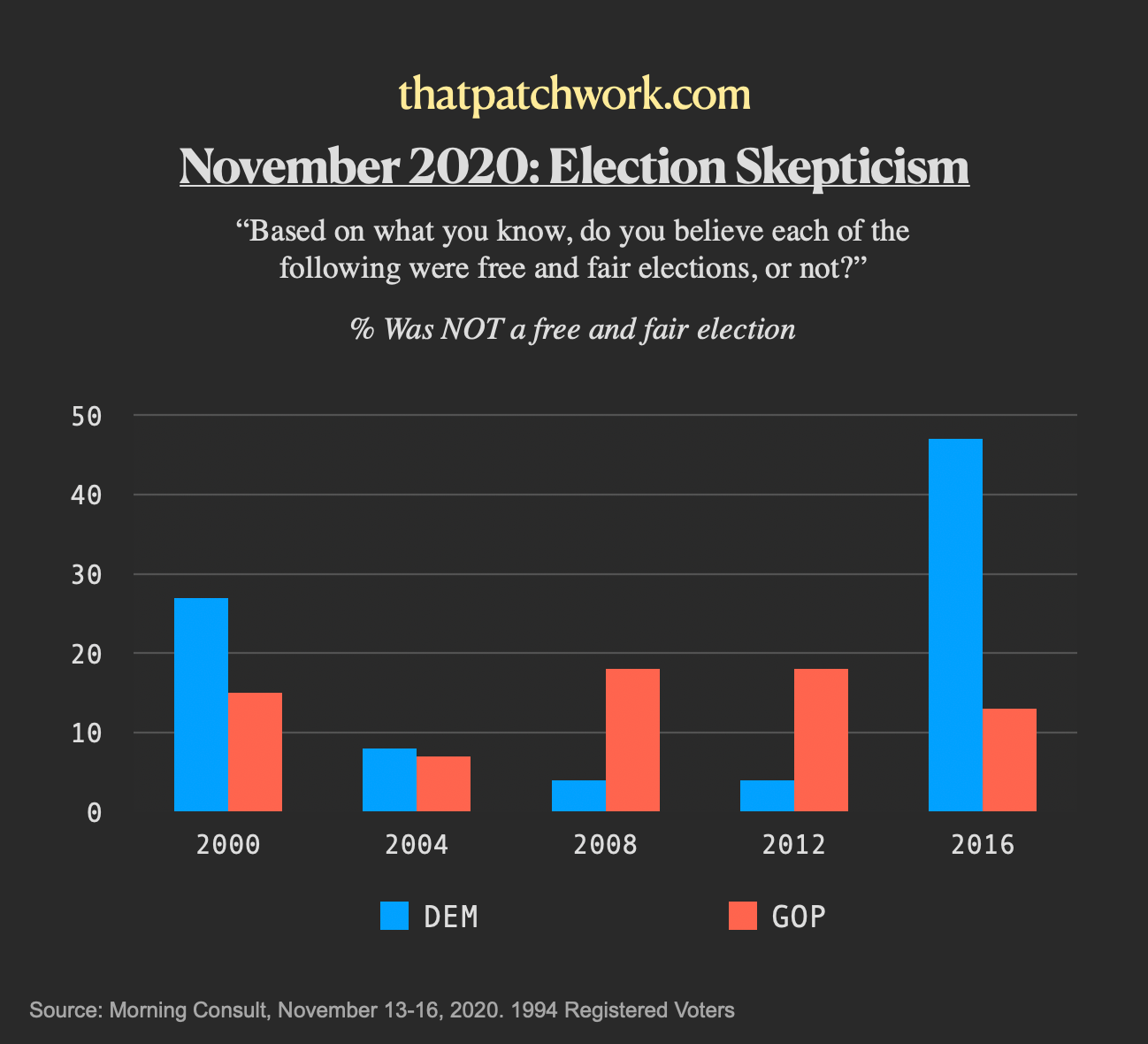

A brief throwback to the presidential election results this century whose legitimacy were questioned.

The false claims made by Donald Trump’s legal team after the 2020 election were fantastical in their unhinged nature, alleging that, along with widespread voter fraud via mail, an international plot involving the Venezuelan government and an algorithm embedded in voting machines engineered a Trump defeat. Trump’s legal team filed dozens of lawsuits contesting various parts of the administrative process in key states, including Arizona, Georgia, and Pennsylvania. In Michigan, officials faced pressure to deny certification of the state’s 16 electoral votes. In Wisconsin, Trump’s legal team and local Republicans sought to block a recount that ultimately expanded Biden’s razor-thin lead in the state. In Georgia, a leaked phone call revealed that Trump pressured Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to “find” enough votes to certify the state’s electoral votes for him. By January 6, largely due to the decentralized structure of the union, all of these efforts failed spectacularly. And yet, when the time came for Congress to certify the results, some two-thirds of the Republican caucus in the U.S. House of Representatives, along with eight members of the Republican caucus in the U.S. Senate, voted to object to the election results from Pennsylvania and/or Arizona.

A poll conducted by Morning Consult and Politico just a day before most networks called the 2020 election but after the ultimate result was widely anticipated found that 66 percent of Republicans believed the election was “somewhat” or “definitely” not free and fair. 76 percent of Republican and Republican-leaning voters cited “ballots were tampered with” as a reason for their skepticism of the 2020 election result.

What a segment of Republican voters believe about the 2020 election is as sensational as it is false and yet not far removed from conspiracies that liberals and reporters advanced about previous elections. There was widespread and irresponsible speculation in the summer of 2020 that the Trump administration, through the United States Postal Service, was working to disrupt the flow of mail ballots to rig the presidential election in Trump’s favor. Many Republican voters believe that anti-Trump actors took advantage of the circumstances created by the coronavirus pandemic, which prompted decisive states to rely on mail ballots, and seized the moment to enable or commit widespread voter fraud to steal a close presidential election—among the very closest in American history. The impact of these falsehoods has been significant and sets a troubling precedent.

That either elected leaders or a significant percentage of the populace has not viewed the result of presidential elections as entirely legitimate is not a new development. Donald Trump took election denialism to a new level in 2020, following 2016, where he established a commission that found no evidence for his claim that widespread fraud by undocumented immigrants cost him the non-binding national popular vote. Democrats, too, have challenged three of the last six presidential elections—or every one of the last six the party lost.

The sentiment that the duly elected president is less than legitimate goes back at least three decades. Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential victory was not contested, but it was viewed by some Republicans, including Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole, as a non-mandate since Clinton had garnered only 43 percent of the vote—the third lowest vote share for a victor, behind Woodrow Wilson and Abraham Lincoln.

In 2000, Democrats famously contested George W. Bush’s election victory in a long-winded and convoluted recount and legal dispute stemming from the vote in Florida. To this day, Democrats remain divided on whether the election was free and fair. About a month after the 2004 presidential election, Democratic Congressman John Conyers called a congressional committee meeting to explore voting irregularities in Ohio, where conspiracists alleged widespread voter fraud tipped the state—and the election—to Bush. In January 2005, with the support of 31 Democrats, Congresswoman Stephanie Tubbs Jones of Ohio formally filed an objection in the House to the certification of Ohio’s 20 electoral votes for Bush. A similar objection was filed in the Senate by Senator Barbara Boxer of California, the lone senator to support the measure. Both objections were overwhelmingly voted down.

In December 2016, when the Electoral College convened to certify election results in state legislatures, amid a groundswell of online and celebrity activism, opponents to Trump implored electors not to award their votes to the Republican candidate. In January 2017, eight House Democrats objected to the certification of the electoral votes. Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee of Texas cited “massive voter suppression,” and Congresswoman Barbara Lee cited Russian interference and voting machine irregularities on the floor of the House.

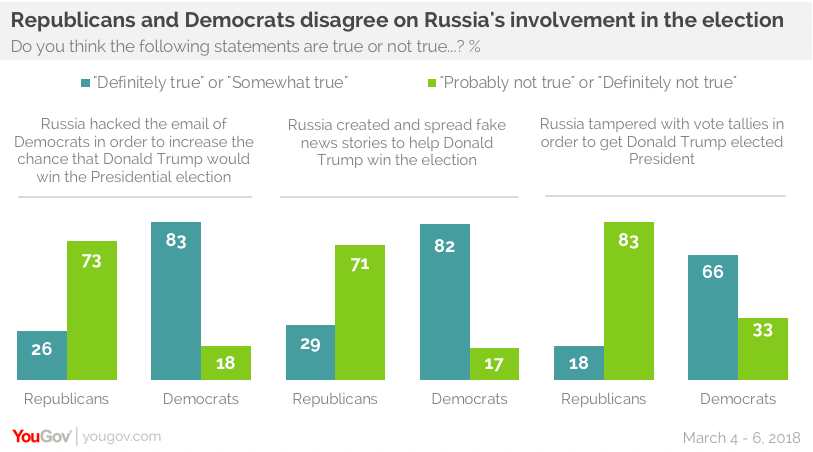

Unlike in 2004 and 2020, none of the objections made it to the floor for a vote. But where Democrats and most mainstream outlets didn’t make wildly false claims about the 2016 election being stolen or stoking a riot at the federal Capitol building, they made-up for that with two and a half years of elaborate theorizing and tinfoil hatery that Trump was elected president because of his campaign’s “collusion” with the Russian government. In the thick of Russigate, the core claim of which turned out to be unsubstantiated, a March 2018 poll found that two-thirds of Democrats believed the Russian government hacked voting machines to change vote tallies in order to elect Trump. These denials may not be objectively equivalent or approximate; that’s fundamentally a value judgment. What does matter is the extent to which election denialism begins to malignantly influence legally-binding legislation, appointments or the function of government beyond the routine politicking and disagreement that are inevitable.

Importantly, the decentralized nature of the Electoral College played a crucial role in fending off challenges to the results of recent elections. By dispersing authority across individual states, each with its own election laws, procedures, and certification processes, the Electoral College creates multiple, independent barriers against interference. This structure made it difficult for any single campaign, group, or faction to overturn results across the necessary states to alter a national outcome. The 2020 election demonstrated this resilience: despite intense pressure on officials in key battleground states like Arizona, Georgia, and Pennsylvania, state and local officials—both Democratic and Republican—were able to uphold their processes, recounts, and certifications with autonomy from federal influence. This patchwork system, although complex, reinforced the integrity of the election by making coordinated manipulation across the nation’s electoral machinery exceedingly unlikely, helping to preserve democratic outcomes even amidst widespread partisan skepticism.

On the eve of another critical election, the shadow of election denialism weighs heavily on our democracy. Both sides have questioned outcomes in recent decades, deepening mistrust and division. As we look ahead, it is essential for leaders and the media, who are our “eyes and ears,” not to undermine the democratic process or the integrity of American institutions.

The denialism of the 2020 election and subsequent elections did provide a stress test for American democracy, one that it ultimately passed. And while the last election did gift us one of the funniest moments in American political history — the Rudy Giuliani press conference mistakenly booked at Four Seasons Total Landscaping near a crematorium and porn shop instead of the Four Seasons — I think it’s fair to say that for democracy we can find our laughs elsewhere.